Proper 24

22nd Sunday after Pentecost

October 21st, 2018

Isaiah 53:4-12

Psalm 91:9-16

Hebrews 5:1-10

Mark 10:35-45

Click here to access these readings.

The first Bible I ever owned was a red-letter Bible that I got in middle school. I probably had a Bible before this, and there were definitely Bibles around the house growing up, but this Bible was the first one I remember having as my own. It was given to me for my confirmation. It was nice, with a kind of fake leather cover in black, and it came with my name printed on it in little gold colors. “Timmy Hannon.”

I really liked this Bible, and for a while it was the only one I owned. I kept it by my bedside for years. I liked the maps in the back of it which were all in watercolor. I liked the pages, too, because they were thin and light like sand or air. And, as I said, it was a red-letter Bible, so that every time Jesus spoke, his words were written in red. So, all of the beginning was just like a normal Bible, all the way up to the New Testament, and suddenly there was this flood of red. Sometimes there was more and sometimes there was less, and I liked thinking of Jesus’s words like the ocean, his voice like a tide flowing in and out. And then, towards the end of each of the gospels, it suddenly turned black again, save for a few words here or there. “My God, my god, why have you forsaken me?” or “Into your arms I commend my spirit.” These stark, red lines in the Bible had a deep effect on me as a young Christian and, in a way, they still do.

Now, I liked these red-letter Bibles. Some people don’t, but I do. And one of the things that’s helpful about them is that they show how often we look only at what Jesus said and not what Jesus did. And this is, of course, pretty natural. Jesus’s words are so full and robust. They’re bursting at the seams with love and joy and hope. We want to drink them in, as if they were water on a hot day, or savor them, as if they were warm tea and a blanket in the winter. Jesus is the Word of God, and we want to know what his words are so that we can feel that love and live that joy and be filled with all that he was and is and will be. Jesus’s words are precious.

But Jesus is the Word of God not only in what he said but also in what he did. We’re reminded of what he did in some of our readings today. We’re reminded of what he did for us on Calvary, of the sacrifice that he made for us – and not just for those who knew him in life or who were present at the crucifixion, but for all people, everywhere, throughout time and across the world. With Jesus’s life, death, and resurrection, he became “the source of eternal salvation,” as we hear in the letter to the Hebrews. We are alive in God because of what Jesus Christ did for us. You are alive in God because of what Jesus Christ did for you.

But it’s not just the big stuff. The big stuff is important, and in a little bit, from Advent all the way to Pentecost, we’ll be talking about the big stuff. But the small stuff is important too, those small, little acts between the red letters that we might often skip over; those small acts of a man who was also God and who was also a man; these small acts that helped to save us.

Look at our gospel reading this morning. Here, we find the disciples preparing for something great that they just know is going to happen. Jesus has been talking about the end, about the fulfillment of their ministry on earth. And where Jesus is talking about his death and his resurrection, the disciples are planning on what is going to happen afterwards. A lot of people in Jesus’s time were waiting for a Messiah that was going to come in with a great army and kick Rome out of Palestine. Many of them were waiting for a great leader or a king, someone who would bring back the days of David or Solomon.

And there’s a bit of anxiety among the disciples, it seems. They’re wondering who will be on top when everything happens. And so James and John, the sons of Zebedee, they go up to Jesus and they ask if they can sit on his right hand and on his left. This question sets the rest of the disciples into an uproar. They surround the brothers, literally “surrounding” them; the Greek is “and they were angry around – surrounding – James and John.” And we, hearing this story, are waiting for what Jesus will say to break up this argument. But the first thing Jesus does isn’t teach them why arguing is bad, or why the last will be first and the last first; he does that, eventually, but not first. No, first he calls them, he summons them, he gathers them around himself. Then, and only then, does Jesus begin to teach.

This calling the disciples, this “gathering” them around himself, this is so very small but it is so very important. It’s not just a stage direction we can skim over. For it says something very important about anger. For when we’re angry about something, we fixate on it. Think about when you get angry – really angry. That thing we’re angry about becomes all-encompassing, it becomes the center of our world. Once, while driving from Tennessee to New Jersey, I was cut off. We were in New Jersey by this time, and we had driven something like twelve hours straight. It was dark and the kids were crying and we were looking for that last exit before getting to my parents’ house. And this guy cuts me off. Oh, I was angry! And in this anger, I started making up stories. I thought, this guy did it on purpose, everyone in New Jersey is so rude, this whole place is filled with angry people, and on and on and on. Anger does this sort of thing (especially when we’re tired). It blossoms into this ugly flower of lies with a stinking fragrance. It becomes the center of frustration and hatred.

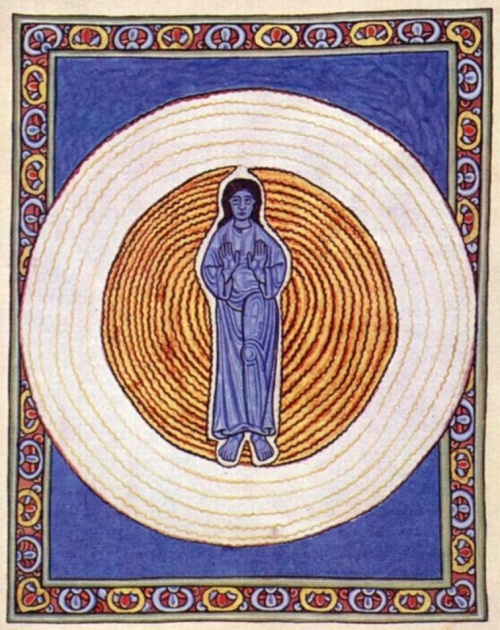

And how does Jesus respond to the anger of his disciples? He doesn’t jump to admonish them and tell them why they’re wrong. That first act, that first response to anger is to call them around himself, to gather them and change what they’re centered on, what they’re surrounding. He takes James and John who are at the center of his disciples’ anger, and he replaces them with himself. Now he is the center, now he is the focal point, now he is the foundation. And while we don’t hear how the disciples responded to this, I assume they quieted down, and were calmed, and they listened. And I assume this because we have recorded what Jesus said. People listened to him when he was at their center and they remembered what he said. People opened their ears and heard what this man who was also God said to them and taught them, because of this simple act of placing himself – of placing God – at the center of their community. And this made all the difference.

Can we do this ourselves? Can we, who are the disciples of Jesus Christ, make that same Jesus Christ our center? Now, our world is a very angry world. Some of that anger is justified, and people should be angry; and some of it is not justified, and it’s scary. But whatever the case, whether anger is justified or it is not, whatever we do needs to be centered on Jesus Christ. And this is the same for all things: our relationships, our hope, our love, our striving and our dreams and the goodness we hope to see in the world – all of it needs, as their center, Jesus Christ. For in Jesus is the Light and the Life; in Him is our Salvation and our Resurrection. All good flows from God through Jesus His Son, the center and very heart of our world. And, like the twelve disciples, we are called, we are summoned to gather around that heart. Let us listen to that voice and heed its call in our lives, for there we shall find the true drink to quench our most desperate thirst.