Fr. Tim’s sermon for the third week of Lent, March 24th, 2019

Exodus 3:1-15

Psalm 63:1-8

1 Corinthians 10:1-13

Luke 13:1-9

Click here to access these readings.

Sometimes, there’s not that much difference between our times and those of Jesus. This isn’t always the case, of course. First century Palestine was a very different place and time than 21st century Coquille. Not only were there no cell phones, but no phones, nor telegraphs, nor even an organized, national postal service. Life was more focused on the family, centered around farms and small towns. There were kings, generals, and emperors. And this is saying nothing of differences in culture or religious worship, everything from how they married and died to how they began a meal. Jesus was talking to a culture much different from our own, and it’s important to remember that when we try to understand what the Bible is saying.

But the people of first century Palestine were human, and there are certain things that all humans struggle with. And one of these common human experiences is tragedy. What do we do when tragedy strikes? How do we deal with our sudden grief, our anger, our sudden, arrested hopes? How do we make sense of the world after a tragedy and, perhaps most importantly, how do we understand God in all of it? Who is God to us now that we’ve been through such grief?

And people in Jesus’ time, just like people today, try to make sense of tragedy and, especially, of God’s role in (or God’s absence) from grief. We hear about a few such instances in our readings this morning, where people reflected on tragedy and asked, “Where is God in all this?” And just as we might wonder about natural disasters and accidents like the floods in Nebraska, earthquakes in Asia, tsunami in Japan, the people in Jesus’ day were wondering just the same things, here about a building that fell on top of people, killing eighteen of them. Such sudden accidents and disasters seem to have no reason behind them. People were just in the wrong place at the wrong time, or the weather just took a nasty turn, or the earthquake came from a place, and at a time, when no one expected it.

And as we reflect, we might wonder, “Why did this happen?” And there are always reasons: earthquakes come from the movement of tectonic plates; the weather in Nebraska was particularly bad this year, the tower of Siloam’s foundation was weak and old. Asking these questions can lead us to answers that, hopefully, can prevent or lessen tragedies in the future. But it is human nature, it seems, to ask not just “Why did this happen?” but “Why did this happen to them?” Why did this tragedy happen to these people? We humans want to understand everything, to make even things that are natural occurrences into things that can fit into a nice, neat, rational box. And so we want to know, “Why them?”

The people in Jesus’ time, and a generation later in St. Paul’s time, were asking just this question. And their answer? Those people who were killed when the tower of Siloam fell on them? The Galileans who Pilate killed? Or those people destroyed by serpents? They must have suffered these tragedies, people were saying, because they deserved it somehow. They must have done something wrong, people thought, and these tragedies, they must have been some sort of cosmic backlash. It was their sin, people decided, that had led them into disaster.

And this line of thinking, as I said, is natural. We humans love figuring out the reasons for things. We don’t just want to know “how” but also “why”. And our faith tells us that God is present in all things, working all Creation to the good. And if this is true, the thinking goes, then it must mean that God wanted these people to die. Tragedy occurs only to those who sin, those who “deserve” it. And so we end up blaming the victims and blaming God.

But Jesus rejects this way of thinking. He challenges those who were gossiping about the guilt of those who Pontius Pilate killed, or about those who died when the tower of Siloam fell on them – Jesus challenges, and rejects, the idea that our tragedies have anything to do with our moral worth. Just as we don’t earn our way into Heaven, but are given salvation as a free gift of grace; so too we don’t earn tragedies and disasters by our sins. Our sins can hurt others, and hurt ourselves, and sins have a great effect on our community and society, but sins don’t necessarily cause towers to fall down or rivers to flood.

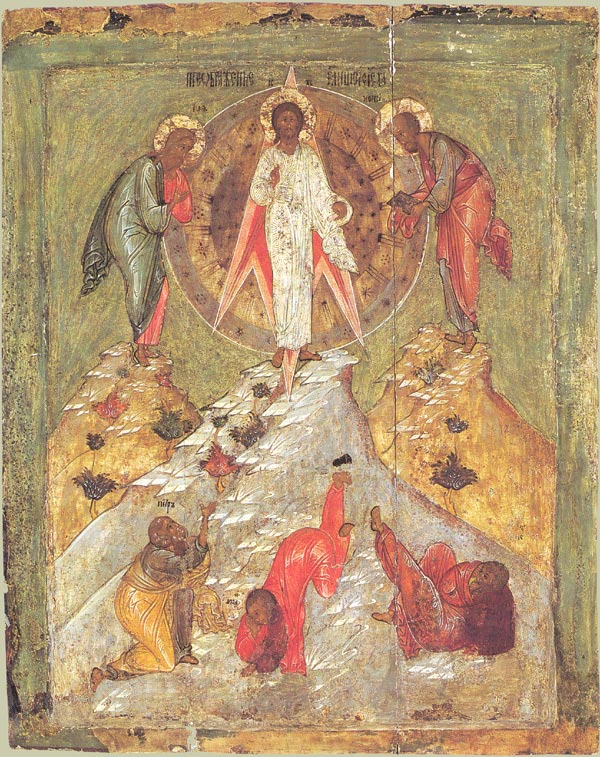

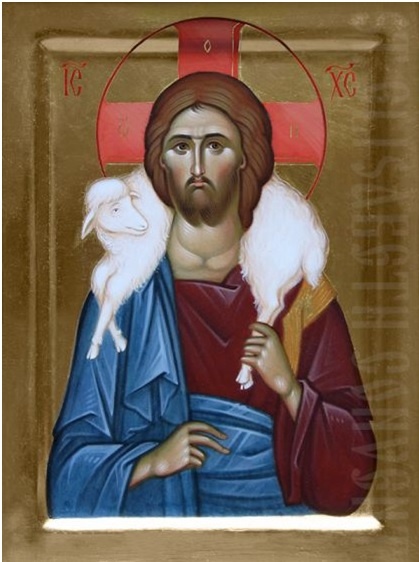

So what, then, does Jesus ask us to do? We are still human, we still want to know “why”, and not just so that we can prevent tragedies from happening in the future. Humans are why to the bottom of Creation and back, and if we can’t blame ourselves or God, then what do we do in the face of these tragedies? Jesus doesn’t say blame, but he says “repent”, which in Greek is “metanoia”, to turn, or RE-turn, to God. This is the same turning we talked about with the baptismal covenant, where we turn from sin and doubt and hatred to love, joy, and grace in Jesus Christ. And this is our call, always, as Christians, that when tragedy strikes, whether it is the falling of a tower or a natural disaster, or even if it is something where a person can indeed be blamed, we are to return to God and refound ourselves in his eternal love. And this is why, on the day we read these stories from Luke’s gospel and St. Paul’s letter to the Corinthian church, when we read about people struggling to make sense of the world, our lectionary also has us read the story of the burning bush and how deeply founded God’s eternal covenant is with us human beings. Our God is not just so powerful that he can move us around like little pieces on a chessboard, but our God is that great being that is the beating heart of all reality. God, the source of all love and hope and joy and all good, true, and beautiful things, is where Jesus directs our gaze and the ground in which he firmly plants our wandering feet.

And yet, we may still ask: sky do tragedies happen? Why do bad things happen to good people, or, if not just good people, then people simply going about their lives, good or bad, trying so hard to be happy? Many generations and many cultures have asked this question, and no one has come up with a perfect answer. But what we do know is this: that Jesus cried at the grave of Lazarus, that God is present with those who are sick, or who mourn, or who grieve, and that after death Heaven shines with a radiant light that knows no sorrow. When we face tragedy, or death, or despair, Jesus says, do not blame. Do not seek reasons in the moral worth of others. Turn to God, for God will not just make your sorrow or doubt disappear, but will plant it firmly in the rich soil of true reality. And there, in the light of Heaven itself, we may find healing, and reconciliation, and hope.