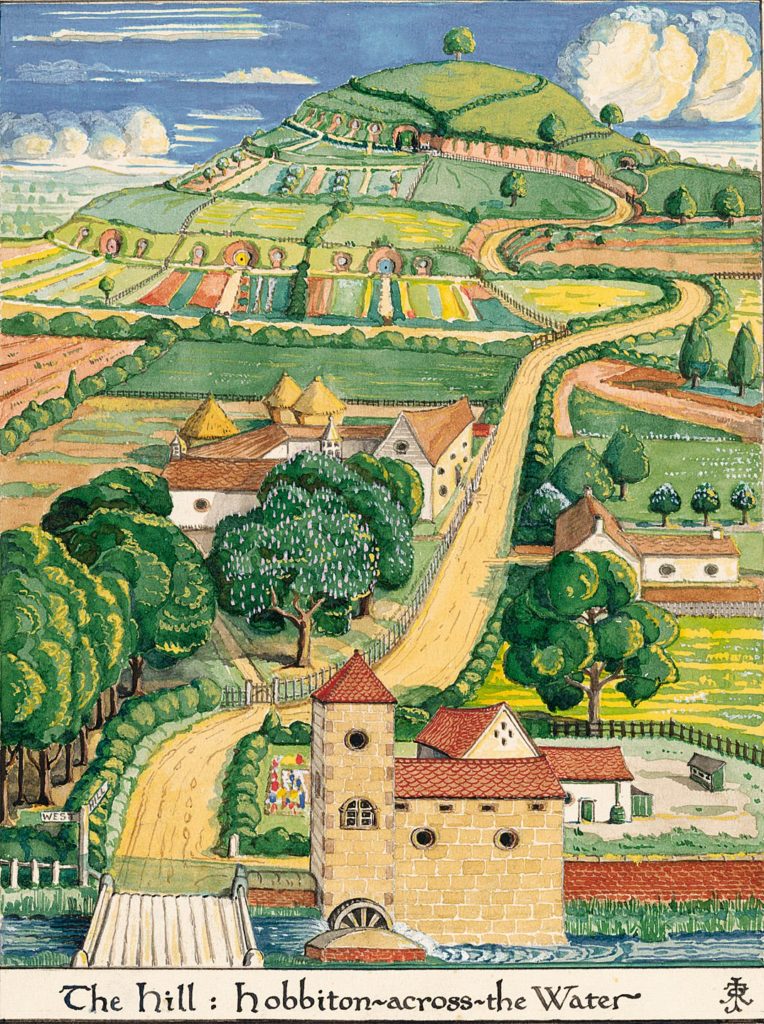

The Hill : Hobbiton-across-the Water, by J.R.R. Tolkien

1 Kings 17:8-16

Psalm 146

Hebrews 9:24-28

Mark 12:38-44

Click here to access these readings.

This morning, I want to spend a little time talking to you all about Hobbits. I’ve not hidden from you that I’m a nerd, but it’s more than my love of fantasy and sci-fi that makes me think of Hobbits when we come to gospel passages like this. For Lord of the Rings is not, of course, out of place in church. The author, Tolkien, was himself a Roman Catholic, and his circle of friends included C.S. Lewis, who was both a great Christian writer and an Anglican just like us. Tolkien called The Lord of the Rings an essentially Catholic work, and while I could go into all sorts of ways that Christianity founds his works, I want to talk this morning about the main characters: the Hobbits.

Now, if you’ve not read The Lord of the Rings, Hobbits are just like us humans, except that they’re shorter in height and rounder around the middle. They’re a small people tucked into the rolling farmlands of the world. Although there are kings and great battles in the world all around them, they seek a peaceful life of the earth. They’re more gardeners and farmers than warriors and leaders. They are a simple people living simple lives.

And the reason I mention them isn’t just because I like talking about Hobbits. You see, when Tolkien was creating Hobbits, he drew on his experiences of common soldiers during the first World War. This was the “Great War” for his generation. It was the war that was supposed to end all wars, and one of the tragedies of World War I is that, after all that fighting and all that death, it only lead to a second, and more horrific war. Tolkien himself was a soldier in France. And while he serving, he saw that the trenches weren’t filled with hardened and grim warriors, but common, everyday people – people he might have seen selling produce at the market or sitting at the pub drinking a pint with their friends. And what touched Tolkien was not just this common-ness, but the bravery he saw in these people fighting against all odds. Even while fighting at the Battle of the Somme, which, if you’ve ever seen pictures of it, looked like a landscape of Hell – even here in these blown-out trenches, even when there was so little hope for coming through alive, these common soldiers held a courage and even a cheerfulness before it all. Simple, common soldiers could do great deeds, Tolkien saw, and in this he also saw the Gospel: people living out the life of Christ.

You see, there is a richness to simplicity. Often, it seems, we think the opposite: simple things are basic, plain, and uninteresting. Simple things are nice as building blocks, but at the end of the day you’ve got to move on and complicate things. Our world certainly works this way: the more complicated things are, the better. Cars have more options, cell phones have more functions. Our systems of government and economics get more and more complicated. And certainly, complicated things like cell phones and computers can do more, but is doing more always a good thing?

I once experienced the richness in simplicity a few years back on Good Friday. Up in Sewanee, they sit in Vigil from Maundy Thursday into Good Friday morning. The idea is that, in the garden of Gethsemane, the disciples fell asleep, and Christ chided them, saying, “Can’t you stay awake, even for one hour?” And so we stay away all night with the Body and Blood consecrated the evening before. In Sewanee, we did this in shifts, so that there’s always someone present, but you don’t wear yourself out and come to Good Friday services exhausted.

So my friend and I had signed up to sit in Vigil from 6 a.m. until 7. It was still dark when we met, and we didn’t say a word to each other, not even in greeting, but went into the chapel together, knelt at the altar rails, and prayed for one, long hour. And it was silent there, so completely silent. At 6 in the morning, there weren’t ambient noises of people going about their day. There was just the simple silence of an empty tomb, and it was powerful. I have rarely known silences that deep.

Then, after our hour was finished, we both stood up and went outside. The sun had risen while we were in the chapel, and the morning was cool and beautiful. And even though our time of Vigil was over, we remained in silence until we met up with Helene for breakfast, and even then words did not come easily. That silence and that presence had stayed with us, so that even a simple phrase “good morning” retained the weight of that hour with Christ’s Body and Blood.

And so when Jesus sees the poor widow in our gospel reading today, when Jesus sees her give just two, small, copper coins and commends her, this should give us pause. The Kingdom of Heaven is found not with kings and princes, great leaders and grim soldiers, but with Hobbits – with common soldiers, in small garden plots, and in two young men kneeling in the silence of the morning. It’s not in great books of commentary but in two people sitting down with only a single Bible between them, wrestling like Jacob with their Scriptures. It’s in simple bread and wine that becomes for us a pathway to the heart of Creation.

And in all this, I’m not saying that complicated things aren’t good, or that we should make do with simple things. Jesus calls us to love the Lord our God with all our heart, and with all our soul, and with all our strength, and with all our mind. There is a glory to digging deep into St. Thomas Aquinas, and there is some poetry that is so wonderfully complex that you can spend all your life with just a few short lines (Wordworth’s Prelude is like that for me). But when Jesus commends the poor widow, he doesn’t say that great acts of kindness are bad but that there is a holiness to the simple and the small. There is a holiness to those soldiers that Tolkien knew, those soldiers who were far from home, who had little hope to survive, who were scared and tired and alone but who went on, with courage and cheer, anyway.

We live in complicated times. Last week there was yet another mass shooting; last week we had elections that seemed to just fuel more arguments. The divisions between us are growing wider and deeper with each passing day. And many are wondering what to do. How can we help? How can we heal rifts, bring people who hate and loath one another together in peace? And Christ’s answer seems, here at least, to be: it is better to light one small candle than to curse the darkness. Pray, do good, and love. And if you have no more hope, then pray from the poverty of that hopelessness. And if all seems dark to you, then do good in that darkness. And if you feel that there is only hatred and sorrow and fear outside your door, then love within that emptiness, for what hatred and sorrow and fear need most is love. For that is what Jesus did: he sowed love where there was hate, he gave of himself when there was nothing left to give. And we, who are his disciples, can do nothing more, nor anything less, than give, and love, and hope with our God.