Isaiah 6:1-8 [9-13]

Psalm 138

1 Corinthians 15:1-11

Luke 5:1-11

Click here to access these readings.

There is a resurrection in our gospel reading today. It’s not the resurrection of Lazarus, where a man who has been dead walks out of his tomb. And it’s not the Resurrection of Jesus, where our savior, having been crucified, is raised from the dead for the Salvation of all Creation. These are grand and beautiful resurrections that shake the foundations of the world. And these miracles as powerful now as they must have been when they happened. But the resurrection we hear about this morning in the gospel is quieter and simpler than these. This of course doesn’t make it any less than a miracle, for it’s the resurrection of a man from despair.

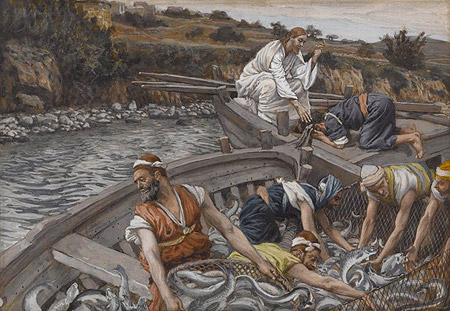

Now, Simon Peter, who we know as the great St. Peter, the one who sees Christ Transfigured on the mountaintop, the one who falls asleep in the garden and who denies Jesus three times, that St. Peter who the basilica in Rome is named after, this St. Peter was, at first, a fisherman. His job was to go out onto the sea, catch fish, then go back, and sell them at the market. And as any fisherman knows, some days there were good catches, and some days there were bad catches. On those good days, he would eat, and on the bad days – maybe he wouldn’t.

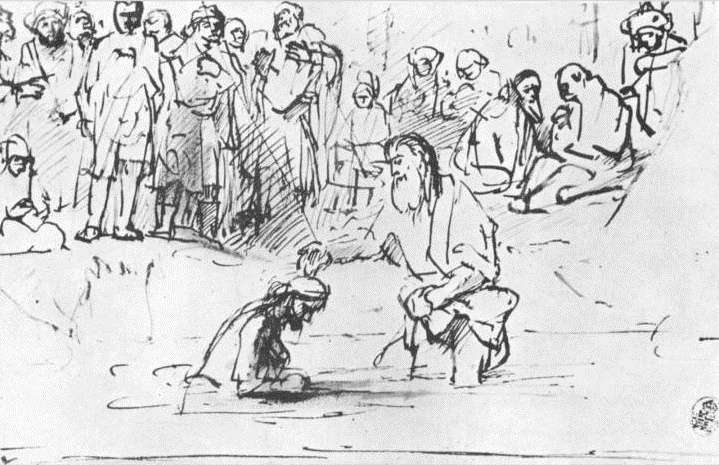

Then Jesus comes, and he performs a miracle. Now, there are many times in the gospels where the people understand who Jesus is. There are times when the skies clear, and they see Jesus clearly as the Son of God. And then their eyes cloud over again, and they forget and act all selfish and proud and deceitful again, but there are times – small times, short moments – when it all makes sense. Peter has one of these moments here in today’s gospel. He sees the miracle of the fish, he can hear the ropes straining against their load, perhaps even the fisherman cheering and laughing aloud at the catch. And he might remember all those times when he came home with an empty boat, and perhaps cursed and hated his trade. And he looks to Jesus, and he sees clearly as a man who can do what he cannot. The miracle strikes him at his heart, and it strikes him perhaps even more deeply because it’s about what he knows best in all the world. It is not just “a miracle” but a miracle about his very life. And he knows that, like Moses with the Burning Bush, he’s standing on holy ground. And knowing this, his legs can no longer hold him, and he falls to the ground.

“Go away from me, Lord, for I am a sinful man!”

Have you ever said these words? Have you ever recalled, with dawning grief and horror, something you’ve done in your life and known, just known that you were a sinner? I don’t know about you, but I have. These are my words just as they are Peter’s. For they hurt us, our sins. Those times when we cheated or lied or spoke words of hate because we didn’t know any better or, perhaps, just maybe, we really spoke them because we wanted them to hurt. And in our pain, in our sorrow from our own sins, we wonder, like Peter, how God can really keep his promise to love us. And that makes the pain even worse.

And yet here – here in the middle of all this pain – is the second miracle. It’s not the miracle of the fish, the one that everyone can see; it’s the miracle of a resurrection inside the heart of this fisherman named Simon Peter. For it is at the moment when Peter pushes Jesus away, that very moment when he shoves away the Lord with shaking hands, that God comes close to him. And it’s important to hear what Jesus says, and what he doesn’t say. For Jesus does not say, “Oh, Peter, get up, you’re embarrassing me”, or “Oh, yes, you are a sinner and you’ve been very naughty, but I can still use someone broken like you”, or even “Yes, well, I’ll just whisk all that sin away for you and we won’t talk about it again.” No, Jesus says, “Do not be afraid; from now on you will be catching people.”

Now, when we talk about spiritual gifts, we often talk about what we’re already good at. We match what skills people have with what is needed in the community, and we call these skills “spiritual gifts.” I can write decently, have an ear for listening, and can lead a group of people, and that’s what you need for being a priest, so maybe I should be a priest. I read a joke online once, where a young person who had a pick-up truck came to church, and the pastor discerned that this person had the spiritual gifts of helping people move furniture. Jack over here is a teacher, so you teach; Edith can speak in tongues, and Ron can interpret them, so you go and do that. And while figuring out what good things God has given us, and using those things for ministry, is important, I think we often forget how much resurrection there is with spiritual gifts.

Here’s a personal story. I think I’ve told it before, but, hey, stories are made to be told twice. When I was in college, I was a horrible public speaker. I was so anxious, and so terrified, that when I had to do anything in front of the class, I panicked. I remember once standing behind a podium and mumbling for five minutes before the teacher had pity on me and sat me down. Sure, I loved talking to people, and I enjoyed teaching in very, very small groups. I don’t know what it was, but the idea of standing in front of people terrified me.

But then, on my first day teaching, all that changed. It was in Japan, and I was led to the front of a class full of eager 7th graders, introduced in a language I was still struggling to understand, then left – alone. There they were, a class full of students, all staring at me, waiting, expectant. I swallowed hard, took a deep breath, and taught. And I was okay. I didn’t mumble, I didn’t cry, I didn’t faint away – I taught. And ever since that moment my fear of public speaking has pretty much disappeared. What happened, I think, is that God gave me a gift – not a new gift, God didn’t give me some skill that I never had. No, he took my love of telling stories or tutoring one or two students, and he enlivened it, renewed it, resurrected it to help me teach more people – and, one day, to speak to others as a priest.

Simon Peter the fisherman became St. Peter the apostle. And Jesus didn’t do this by changing Peter but by renewing him. And this call came when Peter had fallen to his knees in despair. And Jesus takes that despair, and the man on his knees, and lifts them up, and breathes new life into them. And those things over which Peter despaired became the place of his rebirth as a disciple of Jesus Christ.

Now, I don’t often end sermons with homework, but I’ll do so today. This week, take some time and consider how Jesus is working in you. What is Jesus trying to resurrect in you? And I don’t mean just what he’s trying to make new so that you can use it for the benefit of your family, church, and society (though maybe he is). But what part of you have you said, “God probably doesn’t love this part of me.” What have you given up on that, maybe, Jesus hasn’t? What hope, that you thought dead, is Jesus kneeling before and saying, “Do not be afraid”? For we should not forget: Christians are a resurrection people. We are an Easter people. And that means that Jesus – not death, not despair, not tears or pain or sorrow – but Jesus has the last and final word.