Genesis 15:1-12, 17-18

Psalm 27

Philippians 3:17-4:1

Luke 13:31-35

Click here to access these readings.

I want to begin my sermon this morning with thanks. As you know, we flew to New Jersey rather suddenly on a family emergency, and your prayers and words of care were present at every step of the way. In our weekly emails this past week, I wrote a bit on how your prayers and presence during this time of grief grounded us, and I want to say it again, aloud: thank you. In times of death, everything seems unstable and in flux. Your prayers helped us feel and experience God in our grief, and they reminded us of the loving community here in Coquille to which we would return.

And, now, with this sudden trip, I missed the beginning of Lent with you all, and so this sermon will be, in part, a start-of-Lent sermon, but I also want to talk a bit about community, and especially the loving community that we call the Church (capital “c”) and our own church (lower-case “c”), St. James’. We the church, in both senses, are the Body of Christ on earth, and that church is here to care for and love one another and the world into God’s presence. The things that we do – the prayers we pray, the sacraments we celebrate, the ministries we do – all of it is done to lift all humanity and this entire world into the presence of God. And if this seems a great thing, well, it is: for the Church is a miracle, a living miracle of Jesus Christ that turns away from darkness and despair and turns to the light and love of our Creator. And this miracle renews people’s lives, and it renews the world.

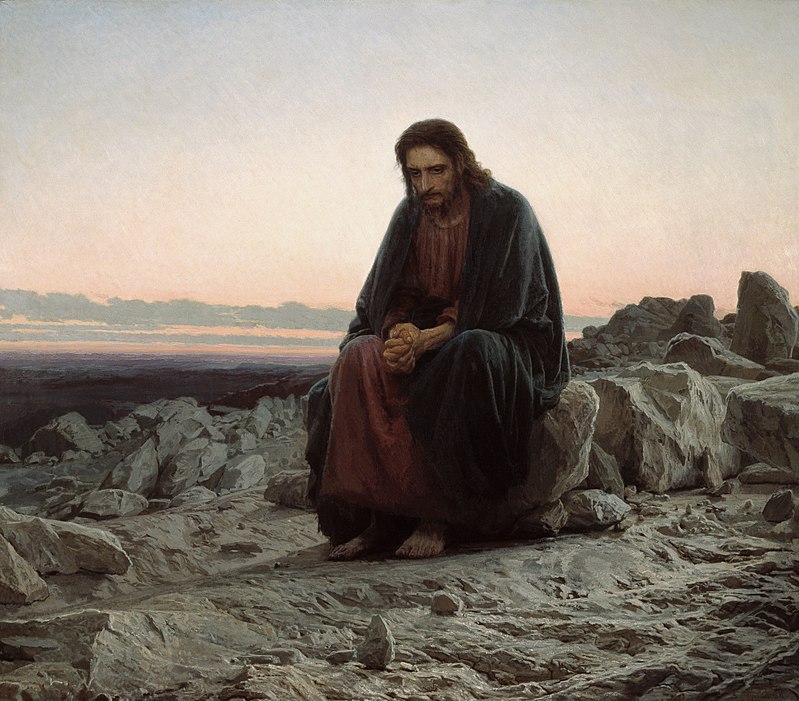

Lent is no different. Lent is also about community/ This might seem a surprise. Lent, as I’ve said, is about contemplation, discipline, and penance, and things like contemplation, discipline, and penance seem like things that we do alone, outside of community. The forty days of Lent – that specific number forty – remembers Jesus’ time of temptation in the desert, where he was alone. If you remember a few weeks back, I printed an image of Jesus in the desert on the front of our bulletin. He sat on a rocky ground, his back hunched over, his hands clasped together, his brow dark. And our own times of darkness are those when we feel alone, either from others or from God. If Shrove Tuesday, or Easter, or Christmas seem like parts of the Christian year where we celebrate as a church, Lent may seem like it’s that part of our tradition that we do on our own.

But this is only seeming, for Lent is truly about the rebinding and the refounding of community. Lent has many roots, but two of the major roots are the preparation for baptism and the rejoining of penitents. So here’s a short history lesson. In the past, the Easter Vigil was the singular time for baptisms, which is why we are baptizing Fiona this Easter (and not on, say, Pentecost, or All Saints’ Day). And this makes sense. What better day to bring someone into the Church than the day that we remember when the whole world was brought into the full glory of God’s grace in the Resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead. Easter is the world’s second birthday, when the whole cosmos was born again into the light of Christ. And we celebrate this, in part, by bringing new Christians into the Church, into our community, into that body of faithful and hopeful people, who, as it says in Acts, continue in the teaching of the apostles, the prayers, and the breaking of the bread.

The other root of Lent I mentioned is the rejoining of penitents. You see, there were times in the Church’s history when certain people who had committed a crime were barred from receiving communion. Such crimes were often a public scandal or some particularly heinous act against the community and the Church. Such people, however, were admitted back into the Church by observing a time of penance. Nor was this penance done alone, but together with members of the community to guide them, and it involved frequent prayers and discipline. This penance came into focus during Lent, and after the forty days, these penitents were readmitted to the community of the church at the Easter Vigil, when they would again join in the Eucharistic feast with their brothers and sisters in Christ.

Now, in the Church today, and especially the Episcopal Church, we don’t observe these bits of culture. Baptisms can happen at any time (Gwendolyn was baptized on All Saints’ Day; I think I was baptized some time in the middle of February), and we don’t really excommunicate people anymore. But what these bits of cultural heritage did give us is a sense that Lent is about the reforming and refounding of community. It is a time when we don’t just take on disciplines to make ourselves better in some vague way, or when we beat ourselves up because (sarcasm) we sinners really deserve it. We do all this because we are preparing for Easter, when we remember when the world was saved from sin and death, sorrow and grief, when we find again the gifts of grace and joy and love planted deep down in our hearts, when we see that all the world is alive with the promises and expectation of the Living Christ – and we want to do all of this together, as the Church, as one body in Jesus Christ our Lord.

Lent is a time of gathering and it is a time of collecting together. And we are reminded in our gospel reading this morning that it is not we ourselves who gather together on our own will and initiative. It is Jesus who gathers us, and not just to gather us and have us all in a single, nice, convenient spot, but so that he may guide us and protect us and love us into Being – together. It is Jesus who calls us out of our loneliness and our despair, who opens his arms wide and says there is goodness and love beneath my wings. Come, Jesus says, come and open your hearts and let me love you, my brood, my flock, my people.

And we are those people, you are those people, who live under the wings of God. And in that love there is healing, and not just healing that sets us back up on our feet and sends us on our way, but a healing that lights a fire in our hearts and our minds and our spirits. It is a fire lit on the day of our baptism, and it is a fire that was lit two thousand years ago on that first Easter morning when the tomb was found empty, and it is a fire lit, a wind breathed out over the chaos, however many billion years ago when all the universe was Created. It is the fire of God Almighty. And our work here in Lent is to turn towards that light and accept it into our heart of hearts.