The Second Sunday of Easter

Readings for this week are:

Acts 5:27-32

Psalm 118:14-29

Revelation 1:4-8

John 20:19-31

Click here to access these readings.

After Christmas, there’s always this discussion of when to put away our decorations. And this is an important question during Christmas because decorations often involve a huge tree in your living room, a tree that is beginning to dry out and get a bit withered-looking. But even still, we don’t want to let Christmas go. We prepared all through Advent, we celebrated on Christmas Eve, we continued celebrating on Christmas morning and during our Christmas nap (I hope you take one of these, too) and at Christmas dinner. But by the New Year, we kinda start to feel that maybe we should put it all away, or maybe at least tone it down. We might let Christmas linger, but by the first week of January, most of us, and our culture included, are looking forward to the next holiday.

Easter is no different, though here in the springtime we don’t have a big evergreen tree to hold us back. We prepare and prepare and prepare all through Lent, then celebrate Holy Week and Easter Vigil and Easter morning and, on Monday, begin to put away the plastic eggs and baskets and little bunny figures. And even if we don’t, even if we keep Easter deep into the Easter season, our culture puts it away pretty quickly. And that’s because, our culture is a culture of anticipation. We look forward to holidays, celebrate for a single day, then move on and, often, forget. What happened last week is not always as important as what will happen next month. If you need any evidence of this, look at all the Easter candy in the discount bins.

The Church, however, does things differently. Holidays start seasons. Christmas isn’t the end of the Christmas season: it’s the beginning, the start of the twelve days of Christmas. Nor is Easter the end of the Easter season. Easter is only the beginning. And we don’t do this just to be different, but because Christians are called on to live not in anticipation but in the presence of God. Christianity is less about looking forward and more about living.

Here’s an example of what I mean. Gwendolyn was born in 2015 and Fiona was born just last year in 2018. And let me tell you, in case you forgot, that there’s a lot of planning that goes into welcoming a new baby into the world. You’ve got to get a crib, and then you’ve got to put it together. You’ve got to have baby clothes and bottles and blankets and stuffed animals that don’t have little sequins or buttons that the baby can bite off. You’ve got to tell your parents and your siblings and your aunts and uncles and your cousin that you haven’t seen in ten years and your best friend from collage, but also the government and the insurance companies so everything is squared away when the big day comes. And when Fiona was on the way, we lived an hour from the hospital, and there was often traffic, so I went out in the car and drove all through the back roads to make sure, in case there was a traffic jam, I could know the perfect way to get Helene to the hospital in time. We prepared and prepared for that one, single day.

And when that one day came, and first Gwendolyn and then Fiona came into the world, I felt a relief and a joy. I was a father, and here were my two little daughters. And now, we thought, with the birth over, we could finally rest and sleep.

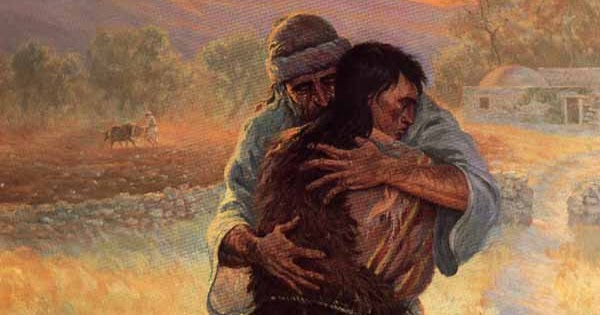

But the thing about being a parent is that you don’t really get to rest, not in the way you do beforehand, that is. Being a parent isn’t just having children; being a parent is about waking up in the middle of the night to feed the kids, to read books to them, to think about their diet and their exercise, who the children are and how you can best encourage and support them. Being a parent is about talking to them about bullies, about how to respect and love others, how to live a life to God, and then to love them even still, and perhaps even moreso, when they fail. Being a parent, like being a Christian, is much less about preparing for the day when the child is born and much more about living a life dedicated to the life of our children; or, as a Christian, living a life dedicated to God.

We do this same thing in the Church for Easter, and the same thing during Christmas and for Epiphany, and for Pentecost as well. And we do this because, just like when we have a child, or when we get married, or when we make our confirmation, in Easter we remember and enter into the new reality that was given to us the morning of the Resurrection. And all that preparation for Easter morning was important, so desperately important, and that’s why we still model our lives on the Jesus’ teaching. But what is important – what is essential to us as Christians, is that the tomb is empty – that Jesus is alive. Because Jesus’ Resurrection was not just about some guy two thousand years ago coming back from the dead, but that in being raised, Jesus poured out Life into this world. And not just once but for all time. The disciples, as we read today, and as we will continue to read, met with the Risen Christ and experienced this outpouring of Life. And in this Life they were moved to speak forth the Gospel and to dedicate their lives to God with a tenacity and a joy that they had never before known.

Nor was it only the disciples who Jesus knew who felt that Life, but it continued to be felt beyond their time and place. In medieval times, people experienced this same Life and were moved to found orphanages, hospitals, and universities, and they were moved to live lives of deeply dedicated prayer. In each age we see again and again, be it medieval or Renaissance or our own time, that Life present and thriving – or, better, causing we humans, who grow weary and tired, causing us to thrive and live to a fullness that we had never before thought possible. And all this because that one man, who was more than a man, but was God, died and rose again.

And it is this Life that we are living in right now. That Life is what we meet in the Eucharist, which is the Body and Blood of that Life, each and every Sunday. And that Life is what was planted firmly in our hearts in Baptism, and what speaks from us when we love our enemies, tend to the sick, give hope to those in despair, and spread the Good News that the Creator of Heaven and Earth, the very foundation of our world, is Love and Truth and Beauty and Goodness.

Easter season, then, is not just about remembering but living the abundance of life that was given to us and all the universe in the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. Easter season is the cup that runneth over from the 23rd Psalm. Easter season is the flowers that are blooming all around us, and just when we thought everything was done, another bush erupts in pink or white. Easter season is having a need for something sweet and looking in the refrigerator and discovering that there’s more cake. Easter season is that scene at the end of “It’s a Wonderful Life”, where people keep on flooding in to tell George Bailey just how much they love him. Easter season is the Eucharist, where the fullness of all Life is poured forth from a little bit of bread and a sip of wine.

Easter season is all these things, and more, because Easter is the true reality. Beyond all doubt and despair, all death and sorrow, Easter is our true home.