Seventh Day of Easter

Today’s readings are:

Acts 16:16-43

Psalm 97

Revelation 22:12-14, 16-17, 20-21

John 17:20-26

Click here to access these readings.

We humans are so often pessimists. We look at situation – be they in our lives, or in the culture around us – and we say, ahh, this isn’t going to end well. We do our best to hope and to keep an open mind, but often there’s that little voice in the back of the head that whispers that everything is going to go south. We do this a lot with the weather – I think a lot of us spent all week last week prophesying rain on Friday and Saturday for the fair – about traffic and delays and how horrible a dinner will turn out. And we know this about ourselves, so much that movie makers take advantage of it with suspense. The other night, Helene and I were watching a sci-fi show, and the main characters were investigating an abandoned ship. They were wandering through the dark hallways, looking this way and looking that, searching for what happened. And it was all so suspenseful, which means that Helene and I both knew that something bad was going to happen: something would go wrong with the ship or some monster was going to pop out and scare everyone. And at one point Helene just said out loud, “Get off the ship! Just get off that ship already!” And in the end, nothing happened, but we felt justified in thinking this anyway. We humans are pessimists.

And it’s not just us in our culture, either. In our first reading this morning, from the Book of Acts, we hear about a pessimistic set of magistrates and a pessimistic judge. Here are Paul and Silas dragged before the authorities in the marketplace. They’re accused of disturbing the city and just being generally un-Roman-like. And what do the magistrates do? They say, “Yeah, sure they’re probably up to no good,” and they have Paul and Silas beaten and then throw them in jail. There’s no trial, no questioning of witnesses, and it doesn’t seem like Paul and Silas get to speak for themselves. The magistrates, it seems, already know the outcome. They’re pessimists. They see these two raga-muffin characters, and, without hearing what they’re saying or seeing what they’re doing, they assume the worst, and throw them into jail. And they probably think they’re justified in doing so.

And then there’s the jailer, who is, really, our hero in this short story. He’s not a hero yet, but he will be. Here’s a man who is, quite simply doing his job. The magistrates tell him to keep Paul and Silas securely, and so he casts them into the innermost cell and fastens their feet with shackles. He’s not taking any chances. He wants to do his job and to do it well. He doesn’t care what Paul and Silas are in for; he got an order, and he’s going to follow it out.

Then there’s the earthquake. Then the ground shakes so violently that all the doors of the prison are thrown open and all the chains are broken. And the jailer wakes up and sees everything that he has been tasked to protect split open and destroyed. And, yeah, I’m coming down hard on pessimists this morning, but your heart really goes out to this man, doesn’t it? Put yourself in his shoes for a moment: your one job in life is to make sure that these doors stay locked. It’s your job to make sure that the doors that hold all these people – all these people that the culture has deemed so dangerous that you’ve got to lock them up – that these doors are now split open and torn from their frames. Imagine working in a bank, and coming in to find all the doors (and to your terror) even the door of the vault thrown open. Or that you come home from vacation and you find your front door wide open. These doors, this vault, these chains, they’re here for a reason, and that is so that things stay inside and definitely not outside. And when the jailer sees all this, he assumes the worst: everyone’s fled away. And then he assumes the worst again: the only proper response is to fall on his sword and kill himself.

Now, when I take this man to task for being a pessimist, I think that he’d do better in being an optimist. We should still criticize this man if, after waking up from the earthquake and seeing the doors thrown open, he just kinda shrugged his shoulders and said, “I’m sure everything’ll be fine.” The cure for pessimism isn’t just a good dose of optimism. This story isn’t here to encourage us to just look on the bright side of life and make the best of what we have. And, to look a bit outside the story, the point of the Christian life isn’t just to move from pessimism to optimism, to just be happy and go-lucky, to look for the silver lining because Jesus has our back and nothing bad can happen to us. No, one of the main points of the Christian life, and one of the main points of this story, is to see clearly, to call for a light, to rush into the darkness, and to see what is actually there.

This is what the jailer does, and what he finds are Paul and Silas, sitting and waiting for him. But that’s not all. He also sees their wounds, fresh from their beating and certainly in need of some medical attention. He sees them for the situation they’re in: that they’re cold, tired, probably hungry, and most likely bleeding. He sees them and, within an hour, has them home, and is cleaning their wounds. And Paul and Silas, in that light, see the jailer, too, and they see what he needs: they speak the word of the Lord to him and to all who were in the house, and they baptize them. And the night ends, not in a dark jail cell, but in the full light of a household with everyone rejoicing in God.

Now, it’s easy to be pessimistic. It’s easy to assume the worst. Or, well, it seems easy. It seems easy because getting your hopes up is hard sometimes, especially when disappointment is so often waiting just around the corner. Once hurt, shame on you; twice hurt, shame on me, as the saying goes. But in being pessimistic, and, really, in being too optimistic as well, we miss what is right in front of us. We miss seeing the problem for what it actually is, and we miss seeing the people in the problem. And, perhaps most of all, we miss seeing the grace of God.

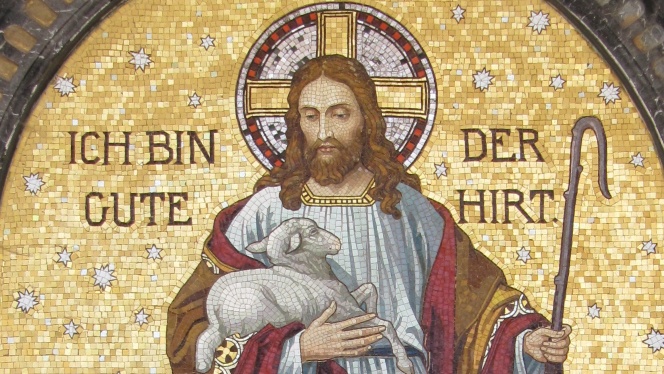

Now this seeing, this act of looking not on the bright side or the dark side, but of seeing, this is something that Jesus Christ was (and is) really good at. Time and time again in the gospels, Jesus encountered people up on life and down on life. He encountered prostitutes and rich young men, he met tax collectors with pockets full of other people’s money, and he met those who struggled every day to glorify God. Jesus met sinners and those who had been blessed. But Jesus looked beyond all this and saw the person, the person himself or herself, whoever they were in the eyes of God. And perhaps most of all, he met them where they were thirsty, where they yearned for something more or better or more holy. He met them at their core, and it was from here, from seeing who they were at their depths, that he sought to heal them and to make them whole.

And, if I can speak for you all, I think we’ve known this sight of God, too. God has looked at us and seen us. He’s looked past the bad and the good, beyond everything who think we are to who we are inside. And God looks with eyes of love – not love that ignores the bad and puffs up the good too much, but eyes of true love, that see us for who we are, which is beloved children of his own making. God lights a candle in the darkness of our own soul, and he picks us up and brings us to his home. And there he tends to our wounds, so many of them self-inflicted, so many of them at the hands of others, but without blame, without hatred, without anger, God washes those wounds with the hands of Jesus Christ and the cool waters of baptism. And then he feeds us with food fit for the soul, that grows Daughters and Sons in the image of his own Son. This is what we experience in the sacraments, in the community that we call the Church, and in our prayers. This is the life lived with Jesus Christ growing inside of us.

And so we, too, are asked to see. Not to hold ourselves back in pessimism or to shrug our shoulders in optimism, but to open our eyes and see the light of Jesus Christ. And in that light, we see those who are hurt, we hear the call from God to go to them, we see the hope of God in his Creation, and we see and experience the healing hands of Jesus Christ, his Son, our savior.