the 14th Day after Pentecost

Proper 18

15 September 2019

Exodus 32:7-14

Psalm 51:1-11

1 Timothy 1:12-17

Luke 15:1-10

Click here to access these readings.

What does the mercy of God look like? This is a great word: ‘mercy.’ We know what it means, surely. You don’t have to pull out your phones and look up ‘mercy’ in the dictionary. You know what it means, but what does it look like? What does human mercy look like, and what does God’s mercy look like.

God’s mercy is shown all throughout the Bible. We see it in the story of Joseph that we’ll read this week for Emmaus Meals; we see it in the story of Jonah and of Ruth, and the story of Naaman who was washed clean of his leprosy. We see it in our Old Testament reading this morning, where Moses asks God to turn away from his anger and look with mercy on the people of Israel. We hear of it in the psalms and even in the prophets, which are so often about criticizing and pointing out fault, but all so that the people around them can be led more fully into the mercy and love of God. Our God is a very merciful god.

And God’s most merciful act was to come to this world in the form of a human being and live among us as Jesus Christ. The life of Jesus, from the first moments of the Incarnation to the Cross and beyond it to the Resurrection, all of it was a mercy of God. God saw that we were in pain, that we humans suffered and were crying out for help. And God came to us and saved us, and not just those who were in pain but even those whose hearts were twisted and corrupted by the sin of hurting others. As Jesus says in the gospels, God came to this world to save sinners. God came in Jesus Christ to save all people, every one of us.

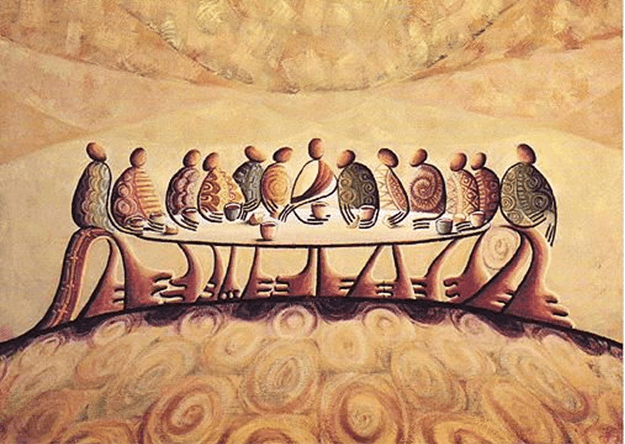

And what does that mercy look like? What does it look like on the ground? Well, in our gospel reading today, it looks like Jesus Christ, the Son of God, the Incarnated Word, hanging out with the worst sorts of people imaginable. Now, we don’t have tax collectors like in Jesus’ time anymore, but, just so you know, these were some awful folks. They were working for the Roman Empire, often extorting money, usually lining their own pockets, but also just plainly working with the folks who were oppressing their fellow countrymen. These were not usually the nicest of people. And yet Jesus ate with them. It’s no wonder the Pharisees and scribes were a bit confused.

Now, this reading here in the gospel – this scene and these two parables – are really important. I think, often, we can get lost in thinking about how sinful we are. We can look at ourselves, look at all the horrible things we’ve done in the past or said in the past or even just thought in the past, and we can wonder, “How in the world could God, who is perfect in any way, love someone as awful as me?” And if we don’t do this to ourselves, then we do this to the world; we wonder, “The world is so terrible. How could God save something this awful?” We beat ourselves and our world up for our sins, we use them as weapons against ourselves. And we imagine that God’s work is to stoop down into the muck that is us so that he can lift us up (with a clothes-pin on his nose because of the stench), wash us clean, scrub us down, hang us out to dry, and all so that when we get to heaven we won’t dirt on the clean, white carpet. When we think this way, we imagine ourselves as stray dogs who don’t really belong with God but that God’s a nice guy and so doesn’t mind all the work he has to do to make us presentable.

But God’s mercy works quite a bit different than that. God’s mercy isn’t the same as endurance or a stiff upper lip. Jesus wasn’t walking around down here with a look of disgust on his face because everyone was so sinful and horrible and he just couldn’t wait until he could go back home to his Father’s. No, Jesus must have walked around with a look of compassion on his face, with an outstretched hand and an open ear. The Pharisees come up to Jesus and they’re all like, dude, how can you deal with those people? And Jesus turns their idea on its head and says, no, you’ve got it all wrong. It’s not that we humans are basically unlovable but God loves us anyway; it’s that God sees us as blessed children who are lost and who need someone to come find them. God does not start with our sins but from three words: “I love you.” And it is from here that all God’s actions, all God’s justice, and all God’s mercy springs.

Now, this doesn’t mean that sin isn’t bad. It doesn’t mean that God is a nice, old, doting grandfather who will buy his grand-kids treats whenever he wants. God’s love isn’t a blind love that just ignores the sin. God knows our hearts inside and out. This is what we mean when we pray, at the start of the service every Sunday: “Almighty God, to you all hearts are open, all desires known, and from you no secrets are hid.” God’s love doesn’t ignore that sin, but God’s love is founded on something much deeper than that. God created us, brought us into being for the pure joy of loving something in fullness and in hope. And that love caused God, when he heard us call out in despair, to come down to this world with his arms wide open so that he could embrace us all.

This changes things, I think. It changes the way – or it should change the way – that we treat others in our ministries, how we treat one another in the church, and how we treat our own selves. And as I’m saying this, I’m kinda preaching to the choir. Over the past couple of weeks, even months, a few people have come through that our culture would rather ignore. But you invited them in, ate with them, cared for them, brought them into your lives in hope to heal them and make their lives better, even if just for an afternoon. Down at the food bank, you laugh with people, you play with them, you ask them about themselves, and you do what you can to help. And when Father Yohana asks for help, you opened your hearts to him as well. You’ve formed a relationship with these folks and you’ve loved them, so that they’re part of our family here at St. James’ Episcopal Church. I commend you all for the love that you have given the lost and lonesome. It is the work of Jesus Christ that you do.

And so I saw: keep loving. Keep loving those people who walk in the door, and those who you meet on the street. Keep loving yourselves, you who know all the darkest places – and the places of most grace – in your hearts and your lives. And when you look out into the world and see more darkness, do not give up hope. Remember that God came into this world to save sinners, to be with us at our darkest moments. God is with us. Never, ever forget that.

And so I stand up here now to encourage you to continue. We’ve opened our hearts here, and things haven’t always gone swimmingly. Sometimes we’ve been hurt. Sometimes we’ve had our help thrown back in our faces. And we’ve learned through some trial and error how to do things better next time. But, no matter what happens, we always stand up and keep going. And we do so not because we have to, or because Jesus did it so I guess we better do it, too. We love others, and we stand up to love others again and again and again, because love is the foundation of reality. And as we live that love more fully, as we live God’s mercy in a world beset by sin and hatred, we become, more and more, that love. For this is the work of God: to form all of us in love, to sustain us in love, and to form us into pure love in the image of his Son, Jesus Christ our Lord.