Pentecost 2

June 23rd, 2019

Today’s Readings are:

Isaiah 65:1-9

Psalm 22:18-27

Galatians 3:23-29

Luke 8:26-39

Click here to access these readings

The other day, Gwendolyn and I watched a scene from a 90s children’s cartoon called the Prince of Egypt. The movie follows the story of Moses, so it’s sort of a children’s version of the Ten Commandments. I’ve never seen the whole thing, myself, but a friend once showed me the scene where Moses encounters the Burning Bush. It’s a really beautiful scene, and I wanted to show it to Gwendolyn.

Now, you all know the story of the Burning Bush: God reveals himself to Moses in the form of a bush that is on fire but not being consumed. Then God issues a call to Moses to save the Israelites from slavery in Egypt. It’s a powerful scene in the Bible, and this cartoon rendition is a pretty powerful one as well. Now, in the scene, Moses is standing all amazed at this strange sight before him. He hears a voice, and he asks, “Who are you?” And God gives him his name, which is one of the center-points of God’s revelation to us: I am that I am. God is pure being, pure love, pure life; that is who he is. And this name reveals that God is not just any other god, like Zeus or Thor or someone, but the God at the center of all existence. That’s quite a name.

But in the scene, God also asks Moses who he is. Or, rather, he tells Moses who he is, but Moses doesn’t believe him. First, he calls out to Moses using his name: Moses! Moses! But Moses barely answers. Then God says that he will send Moses to Pharaoh and set the Israelites free from their slavery in Egypt. Moses comes up with all these excuses of why he shouldn’t be the one, but God just says, no, it is you who are to go. In short, God says: Moses, this is who you are; Moses responds by saying, that can’t be.

Now, this film isn’t the Bible, but I think it does a great job of picking up a really important theme in our Scriptures: who are you? Time and time again in the Bible, God asks a person, “Who are you?” or, perhaps more appropriately, “Is this who you really are?” It happens often when God calls someone to a specific task. When the Jeremiah is called to be a prophet, he says, “You can’t mean me; I’m just a boy!” Jonah does it better: when he’s called, he doesn’t just say “no” but turns tail and runs the other way. But it’s not just when people are called to some great task that God asks them, “Who are you?” God asks this to King David when he commits first murder, then adultery: “Is this who you really are?” And Jesus asks it to St. Paul when he first appears to him: “Why are you persecuting my people? Is that who you really are? Or are you someone more?” And Jesus asks it all throughout the Gospels as well: to the woman at the well; to a bunch of fisherman who then become his disciples; to St. Peter in that beautiful story at the end of John’s Gospel, though here Jesus doesn’t have to ask the question directly. Instead, he asks to Peter (three times to balance his three denials of Jesus): Peter, do you love me? And when Peter responds “yes”, each time Jesus tells him: “Feed my sheep.” In other words, he’s saying: if you love me, Peter, if you are one of my disciples, then here is who you are: feed my sheep.

Now, we’re asked “Who are you?” pretty much all through the day. When we go to the doctor’s office, especially if we’re a new patient, we have to fill out these long forms that ask us our name, our address, our closest-kin, our medical history, and on and on. When we sign into our email, we’re asked for our user name and password. Some larger churches have name-tags so that everyone knows that this is Joe and this is Frank. And I don’t know about you, but I get tired of all this. And all I want is to go to a place like in that old show “Cheers”, where everyone knows your name, where people know who you are deep down to your core. That’s one of the beauties of a family: they know us, through and through; or one of the deep graces of your home church: when you walk in the door, or when you see one another out in town, you know them, you know their pains and their joys. You know what they’re going through and what they’ve gone through. You know them.

And how much moreso with Jesus. There’s a great prayer at the beginning of our Sunday liturgy; it begins: “Almighty God, to you all hearts are open, all desires known, and from you no secrets are hid.” Now, I’m not required to say this prayer each week. It’s one of those optional prayers, but even so, I always make sure to begin the liturgy with this prayer. And I do so because I think it’s important to remember just how close God is to us, just how deeply and thoroughly God knows us, and that he still loves us and is dedicated to that love. Because the presence of God, the mere presence of him, be it in the Bible or the history of the Church or in our own lives, God’s presence strips away all that we think we are, all that we write on those forms in doctor’s offices, all the user names and passwords, all the titles we put before our names or the letters after them, and gets down to the nitty gritty of each of us. And who are we before God? When God has seen through all of our smoke-screens, all of our mind-games, what does he see? Nothing more, and nothing less, than his own beloved children.

That’s a lot. I could stop right there, and we could all sit for a while to drink that in, because that’s huge. The Creator of Heaven and of Earth, of all that we see and know, and all the angels in the heavens, the ruler and life of all that is: loves us. Thinking about this, you can maybe understand why some people become monks and nuns, so that they can sit and ponder and work within this great reality all the days of their lives. But what can we do with this awesomeness, this great grace that the Lord God Almighty loves such creatures as us, and loves us so much that he would take the form of a human and die on a cross?

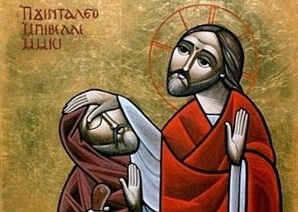

Well, one of the things we can do is to ponder this reality, to pray within this reality of love and goodness. But Jesus gives us something more as well. At the end of our gospel reading this morning, look at what happens: the man, once enslaved by a legion of demons, is now whole and healed, and he wants to go with Jesus. But Jesus sends him back, and what does he say? “Return to your home, and declare how much God has done for you.” Tell people about God. Tell people about your life with God, and your life lived in God’s love. Tell people about where you meet that love: in your garden, with your family, volunteering at the food bank, here at church. Proclaim God’s love in the world. You don’t have to stand on the street corners and yell at people that God loves them (actually, I’m pretty sure Jesus told us to be cautious of doing this), but we are called to not just keep God’s love to ourselves but to share it, to open our arms wide and share our story of our walk with God.

We are Spirit-spreaders, we Christians. So cast those nets wide, sing your songs loud and with a full voice, and love your God with all that you are. For God loves you for all that you are, and more.