Exodus 34:29-35

Psalm 99

2 Corinthians 3:12-4:2

Luke 9:28-43a

Click here to access these readings.

Okay, it’s time for another field trip in the BCP. Can you all pick up your red BCP and open up to page 363. Now, look down at the bottom of the page. Do you see those two little phrases there, one right next to the other, is two columns. There’s something interesting that happens here, and it’s always made me smile.

Now, this is right after the Eucharistic Prayer. We’ve heard Jesus’ invitation to us (“Take, eat, this is my Body”), and the priest has consecrated the bread and wine. We’ve proclaimed the mystery of faith, and we’ve all said the great AMEN. And here, at the bottom of 363, we have to choose one of these two phrases to say, though they both basically say the same thing. We here at St. James’ choose the left side and I say, “And now, as our Savior Christ has taught us, we are bold to say.”

Now, when I was first coming into the Episcopal Church, this phrase always made me smile. Because it’s rather grand, isn’t it? This word “bold”; it makes this sound like Star Trek: “to boldly go where no one has gone before.” And I liked that. There is a power to the phrase, and a joy. I felt like the priest was saying to me, “Get ready! This next thing is gonna be big! Time to be bold!”

And what was this phrase preparing us to say? What’s the next part of the liturgy? [wait for answers]. That’s right, the Lord’s Prayer. This surprised me. I wondered, at the time, “What is so bold about the Lord’s Prayer?” This was my good-night prayer. My parents taught it to me before I was in elementary school. I could rattle this thing off without even thinking of the words; what’s so bold about saying the Lord’s Prayer?

Now, this word “bold” here is important, and that’s one of the reasons we use it here at St. James’. First of all, here in the liturgy, it’s a sort of marker. If you flip to the next page, you’ll see two different translations of the Lord’s Prayer, one in traditional language, the other in contemporary language. And you, the people, know which we’ll use by whether I say “we are bold to say” or “we now pray.” So “bold” is a sort of liturgical marker to help you all along with a liturgy that can be, at times, complicated. I use the traditional translation, because I like its theology better, and so I say, “we are bold to say.”

But I say “bold” for another reason. Think about this: God Almighty, the Creator of Heaven and Earth, who made everything from the Sun in the sky to the tiniest little one celled organism, who sustains our life and leads us to eternal salvation, came down to earth as a human being and taught us how to pray. And the way he taught us to address God, the Ruler of All Things, basically, was to say, “Daddy.” There’s a boldness to this. There’s an audacity to looking up to the Creator of Existence and saying, “Hi. I’m hungry, and I’m sorry. Please be with us forever.”

Early Christian leaders were in awe of the Lord’s Prayer. They called it the perfect prayer, and some early writers even considered it one of the Sacraments. Every single type of prayer, from intercession to thanksgiving, is found in the Lord’s Prayer. And it was spoken by Jesus Christ himself, our Lord and our Redeemer, the man who joined Heaven and Earth and brought us eternal salvation.

When I think about this, when I think about all the history of this prayer, the holy lips that first spoke it, and the eternal Being that I address when I speak it, I feel in awe, and I hesitate. It seems too much for me, I who am so small, just a single man who is trying his best to be a good Christian. And I’m not alone in feeling this, because I think it’s something of what Peter felt when he saw Jesus Transfigured on the mountaintop.

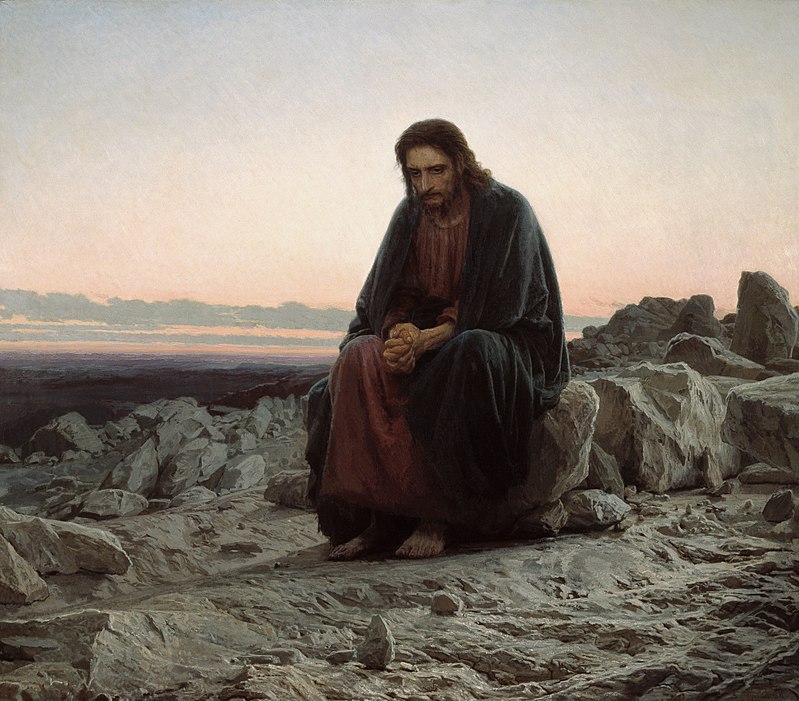

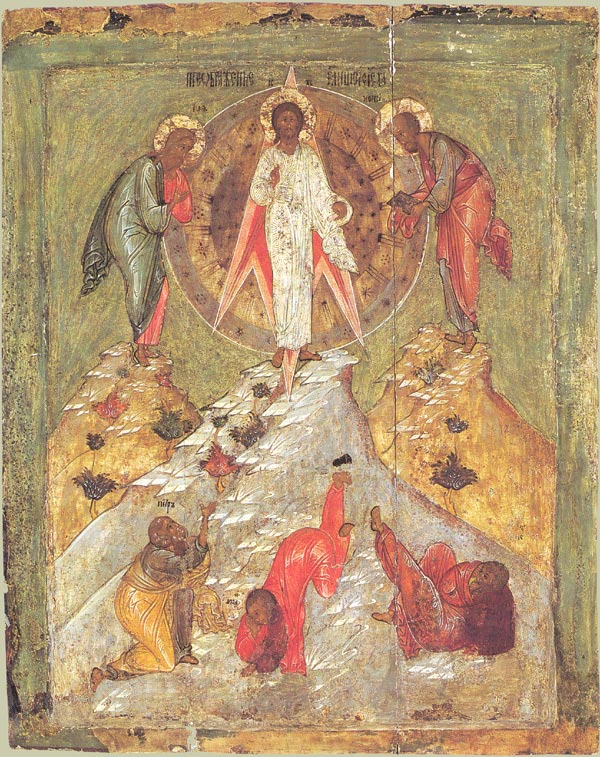

You see, Peter is also struggling to understand the power and the grandeur that’s right in front of him. Earlier in chapter nine of Luke’s gospel (where we are in our gospel reading this morning) Jesus takes five loaves and two fishes and feeds five thousand people. He then tells the disciples that his road isn’t to glory, but to death, and a pretty nasty one at that. And he also tells them that if they really want to follow him, whoever really wants to save their life, they must lose it. And if that’s not enough, up on a mountaintop, Peter and John and James witness Christ revealed, in all his heavenly splendor. Their heads must have been spinning. This guy who they’ve been traveling with, this man who they’ve been eating with, sleeping next to on the dusty ground, trudging under the hot sun with, and probably complaining to, this guy is not just a guy, but God Almighty, here in the flesh. On the front of your bulletin is an icon of this scene, and in it, one of the disciples is so amazed that he’s fallen on his back with his feet up in the air. His world has turned upside-down.

And Luke doesn’t record it, but I wonder if, after the Transfiguration, after they’ve come down from the mountaintop, the Peter, James, and John gather together and wonder what to do. “We’ve just seen God, all but face-to-face. How do we go on? How can we just sit down next to God himself and eat a bit of bread, or fall asleep around the campfire next to him, or wake up in the morning without constantly falling to our knees and worshipping him”. I’m not sure if the disciples wondered about this, but I know I would. Here is a piece of Heaven on earth; how do we go about our normal lives in front of him? Or, thinking of the Lord’s Prayer, another piece of Heaven on earth, how can we just say it, knowing the holiness from which it came?

Now, if this worry bothered the disciples, it certainly didn’t bother Jesus. Because look at what happens after they come down from the mountaintop: Jesus is back with the crowd, back with those who are hungry and scared, sick and in need. A man comes up to him, shouting, probably not just to be heard but because of the pain in his heart, begging Jesus to heal his son. And what does Jesus do? Jesus who just yesterday stood as God on the mountaintop? He invites them in, and he heals the boy, and gives him back to his father.

And, maybe, maybe Peter realized something when he saw this. Maybe he saw that holiness doesn’t mean falling on your face but opening your arms. There is a boldness to saying the Lord’s Prayer, surely, but it is a boldness that says, “God, the Creator of Heaven and Earth, and of all things in the cosmos, whose voice is contentment, and whose presence is balm, our God: is here.” Our God is not some distant being, off somewhere beyond all knowledge, checking in on us every once in a while to make sure we’re not ruining the place. No, our God is with a young boy who is sick, and his father who has nowhere else to turn. Our God is with poor, the sick, those who mourn, the meek, the peaceful, and the merciful. As one of our collects at morning prayer says, “Lord Jesus Christ, you stretched out your arms of love on the hard wood of the cross that everyone might come within the reach of your saving embrace.” Holiness is the presence of God in the very fabric of our lives.

In seminary, we were introduced to a bunch of different Sunday school curriculums. Each of them were good in their own way, but one I really liked. It instructed kids on how to be Episcopalians, and so it taught a lot about the liturgy, about the sacraments, and the church year. And, when teaching about the Eucharist, it encouraged the teacher to use the actual vessels that are used in the church service. You know, the expensive, highly breakable, glass vessels. At first, I was really anxious about this. I knew these things were going to break. The kids would pick them up, and not even by anyone’s fault, they’d drop them and they’d break. And the instructor said, yeah, sometimes they break, but actually, this is how kids learn about holiness. They pick up holiness and they turn it in their hands. And she said, the reverence these kids have for these vessels, and for the Bible, and the altar, and, really, for God, is amazing, because they could touch them, use them, see how we treat them Letting kids touch these vessels was inviting them into that holiness.

Nor is this lesson just for children, but for us adults as well. God has invited us into the holy through Jesus Christ.