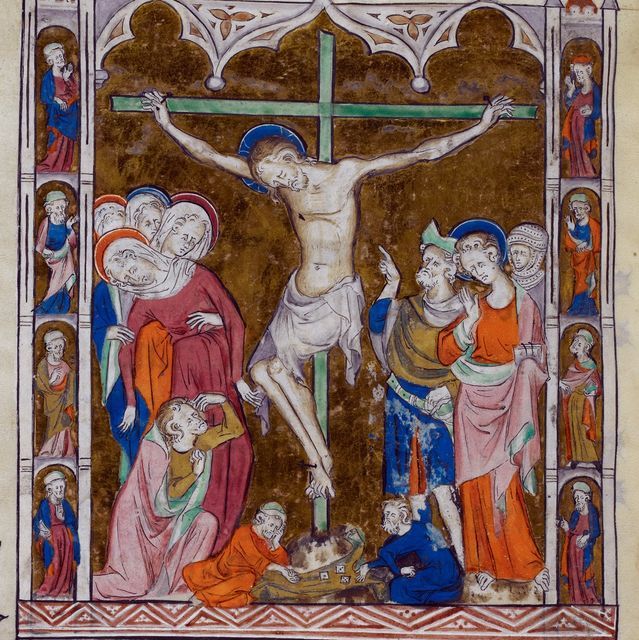

Jesus and the Rich Young Ruler, Heinrich Hofman, 1889

Proper 23

21st Sunday after Pentecost

October 14th, 2018

Amos 5:6-7, 10-15

Psalm 90: 12-17

Hebrews 4:12-16

Mark 10:17-31

Click here to access these readings.

Two summers ago, I met a guy while doing my hospital internship. He was one of the other chaplains and was a Roman Catholic seminarian. And this guy, Matthew, had a pretty interesting story. He grew up as a Presbyterian and, in his early thirties, converted to Roman Catholicism. And for a while, Matthew served as a Franciscan monk in New York City. There he heard a call to the priesthood, but even when I met him, a few years after he left the monastery, he still had those usual monkish qualities to him: he was calm, quiet, and yet with a powerful presence. And he was incredibly intelligent, too. But, unlike most people who are bookish, Matthew didn’t have any books. In fact, Matthew only had, only owned, as much as could fit in a small cardboard box. This was a discipline of his, and he kept it pretty strictly. Once, he brought over two books to give to me, out of the blue, because they wouldn’t fit in the box anymore. And once, when I saw his rosary and showed some interest in taking up the practice, he frowned, looked at it, and gave it to me. It was from Jerusalem, he said, and I could tell that it meant a lot to him. I tried to give it back, but he put up his hands and said, “No, you keep it. If the Spirit has guided you to an interest in it, who am I to keep it for myself?”

Now, when we hear the story in today’s gospel reading, where Jesus tells the young rich man to “go, sell everything you own, and give the money to the poor…then come, follow me”, when we hear this story, I think we all wonder if we have to be like my friend Matthew. Imagine taking everything you own, every single thing that you can’t throw on your back or, at least for my friend, in a single, small cardboard box, and giving it all away. Helene and I had to do this once when moving from Georgia up here to Eugene, though we came with as much could fit in a little Dodge Neon. A different friend of mine, whose parents were in the military, said that whenever they moved (which was a lot) they threw out everything they owned and bought new things wherever they landed. It was cheaper that way, he said, than to haul tables and chairs and clothes and nick nacks all the way across the country. And, anyway, it helped you keep from getting attached to things. Imagine doing this yourself, and you might have a sense of why this rich young man may have balked at what Jesus asked him to do.

But, if we were simply to sell everything we had, to give it away, I think we’d be missing the point of our gospel reading. Few, when we go to the Bible, we don’t find a list of things to do but a collection of stories about people. And not just any people, but stories about people who meet Jesus, who meet God on earth, face to face. And in these stories, Jesus challenges people to examine their lives, to look at who they are in relation to others, to the world around themselves, and to God. And what we have here is a story about a man who is ready to give up everything for God, except – and it’s this “except” that is the important part of the story. Jesus saw this man’s “except” and he brought it forward, not to scare the guy off, but to challenge him to a deeper faith, and to show the man what it really means to seek after eternal life.

And this is our challenge as well. For what my friend Matthew did when he gave me his rosary, and what Jesus is calling the rich man to do, is a bit deeper than just giving your things away. Anyone can do this, and some of us can do it very easily. We’ve all got a bit of clutter in our lives that we could easily (and happily) do without. Even after moving and paring down, I can look around our house and find quite a few things that I don’t really need: books, clothes, even furniture. I just keep it around because I like it, and it’s nice having things. If I met someone who needed them, really needed them, I don’t think it would hurt me much if I gave them away. And in this gospel reading Jesus is saying, yeah, sure, but what about those things that you feel you couldn’t live without. What about all your books on Tolkien that you love so much and put in special boxes when you moved? Or that nice red stole you have that says so much about your love of medieval Britain? Or those pictures of Gwendolyn and Fiona when they were just a few days old? What if I asked you to give those things up to be my disciple? Would you still stand up, drop your nets, and follow me?

Since I’ve gotten here, over the past three months I’ve been preaching on the Christian life, of what it means to be disciples of Christ. For our soup suppers I’ve called this “ever-deeper conversion”, for we are always seeking to deepen our relationship with God, always trying to become better disciples. And we need to reflect in this way because we humans are so good at putting up road blocks on our own walks with Christ. We take things in our lives – or not just things but people, or titles, or ideas – and we think, “This completes me. This is who I am.” I am a father, or a priest, or a friend who listens well. This photo of Gwen, or this beloved book, or even this collar, defines who I am as a person. While in academia, I remembering thinking to myself, “I am a scholar, and I can’t imagine myself as being anything else.” I thought I had figured myself out, and before I could really do discernment for the priesthood, I had to remember that what I really was was not a Scholar but a Child of God. Everything else flowed from there.

What are those stumbling blocks that we have put between ourselves and God? What are the “except”’s that we cannot put down and that Jesus is, even now, challenging us to see for what they are? What are the idols of our own making in our own lives? These are difficult questions, but there is a freedom in these questions that we don’t often see. For we are bound up with these idols. Idols aren’t just bad and sinful because they are not God and it’s bad not to worship God. Idols are sinful because they control us, they make us think that they encompass all of reality, that they, in their limitedness, are actually ultimate. We clutch on to them and fixate on them, as if they were all in all. But God reaches out, and he takes our trembling fingers, and opens them up with his own firm hand. And we turn, ever so gradually, often resentfully, but ever so gradually, to a larger and more beautiful world. Here we are given the freedom to love things for what they are, and not for what we force them to be. Here we see that the thing that defines us, the thing that is truly ultimate, is not us, but God. For in God, everything is in their proper relationships. In God, we may give with hope, receive in love, and walk ever in the light of salvation.