Trinity Sunday

16 June 2019

The readings for this day are:

Proverbs 8:1-4, 22-31

Psalm 8

Romans 5:1-5

John 16:12-15

Click here to access these readings.

Let’s start this morning with a field trip in the BCP. Could you grab your red Book of Common Prayer and turn to page 307, please. It’s right at the bottom of the page, marked with a nice big heading “The Baptism.” Now, this section is right smack dab in the middle of the liturgy for Baptism. This is where the actual baptism happens. The part in italics (called the rubrics) tell us that each candidate is presented by name, then each person is immersed or has water poured over them. And while they are in the water, these words are spoken: [person’s name], I baptize you in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.

Now, why do we do this? Why do we, when we bring people into the Church through the Sacrament of Baptism, do so in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit? Why not just “in the name of God”? Why use God’s name at all? Well, the easy answer is that Jesus told us to do this. In Matthew’s gospel, Jesus tells his disciples to go out and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. But as we do this, and do it faithfully and joyfully, we may also ask: why? Why do we baptize in the name of the Trinity and not in some other way?

We Christians believe that the true nature of God is found in the idea of the Trinity. God is One, but God is also Three. And God’s how we might be when we’re in different groups, so, even though there’s just one of us, we act differently with our families, our friends, and out in public. And it’s not as if God is a set of three identical triplets, each that looks very much alike but, at the end of the day, are really just different people. No, God is One and God is Three.

And if this makes your brain hurt trying to imagine how God can be both One and Three at the same time, don’t worry. The Trinity is a very complicated, often confusing part of our faith, and many good, intelligent people have spent their whole careers trying to find different ways to explain something so beautiful. That said, the Trinity isn’t something big and complicated like, say, the motions of the planets or the tectonic plates, that if we think about them for a long time, we’ll be able to fully understand them. But when we look at our lives, and when we look at what is revealed to us in Scripture, when we listen with our hearts and minds and souls, we begin not just to understand that Trinity but to live it, breathe it, and walk in it.

Our readings this morning are part of this revelation. Now, historically, the concept of the Trinity – the idea of it – was not thought up until the fourth century. Christians in the fourth century were very much concerned with the exact nature of the relationship between Jesus and God the Father. And one of the things produced from fourth century discussions is the Nicene Creed, which can be very technical at times with its language about “God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten not made, of one Being with the Father.” But all of these discussions weren’t just vague philosophizing and people making up theories off the top of their heads. No, these early Christians were drawing the understanding of the Trinity from how God had revealed himself in Scriptures – in what we call the Old and New Testaments – and in the life of Jesus Christ.

We see some of this revelation in our readings today. We see it in our reading from Proverbs, where the Wisdom of God stands like a master worker at the founding of the world. And this Wisdom isn’t just being wise but seems to be a person, a being, for God delights in him, and Wisdom rejoices in God and the world that was created, and humanity with it. And in Romans, St. Paul describes God’s life as being love poured out into our hearts by the Holy Spirit, bringing to us a peace – even in suffering – through Jesus Christ. St. Paul doesn’t tease it all out for us, or separate all the components of God like a little kid at school lunch who takes apart each piece of his sandwich; but instead he says that the life of the Father and Jesus and the Holy Spirit are intricately intertwined. For the language lovers of you, God is not just about nouns but about prepositions for St. Paul. God’s about ‘through’ and ‘in’ and ‘with’ and ‘inside’, about poured into and living with and given through, so that God is revealed to be not just some bearded guy on a throne with people at his feet but a being of living, breathed life and who pulls us into that life so that we may be healed and sanctified into that relationship.

And there is, of course, Jesus himself: his words and his deeds and his very being. Time and time again Jesus speaks, acts, or directly identifies himself with God the Father, and the Spirit together with them. Jesus, and God, and the Holy Spirit are, in some way, revealed to be in an intricate relationship with one another. And it was this relationship that the fourth century councils, through reading and contemplation and prayer, came together to write the creeds.

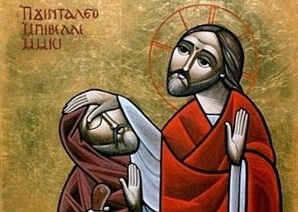

But we don’t believe only because the Bible and the Creeds tell us to do so. The Bible and the Creeds are an authority in our lives as Christians, surely, but they themselves live and breathe in the context of our faith here in the present. For we see, even in our own individual lives, that the God of the Bible and the God of the Creeds is still alive today, grounding us, healing us, and breathing new life into us. We experience God the Son, God in Jesus Christ, in those times when we find healing and goodness in the most turbulent of times. When we turn from our own darkness, when we turn from hatred or disdain or sorrow, when we are caught in that darkness and hatred and disdain and feel a steady hand turning our hearts towards light and life and goodness; that it is the life of Jesus Christ born within us doing this work.

And in this healing, in this turning from despair and darkness, we are not only led back to a sort of status quo but are lifted higher into light. This is the work of the Holy Spirit, who won’t let us remain in complacency, but will show us a deeper life, a fuller life, a more hopeful and giving life that is ever the promise of God. And this life is founded on something strong, something sure, something that will never move, something that is not a “thing” but is the Creator and Guider of all Creation, a being of truth that will never stop loving us; and this being we call God the Father. And all this work of God, the work of Jesus and of the Spirit and of the Father, all of this is to bring Creation into a fullness where there is no grief or despair, no hatred or resentment, but goodness and love for all eternity.

We as Christians have dedicated our lives to this Trinity. In Baptism, whether we were baptized as a child or led into the faith by others, in Baptism, we were all brought into the Church; in the Eucharist we meet Jesus and are healed with his hands of love; in the Sacraments we are nurtured into the Life that was born and is growing within us; and in our mission, our good work as the Church, we bring that Life out into the world that is so deep in hurt and sorrow. For that Life that we have seen in Scripture, and that the Church has proclaimed for the past two thousand years, is here now in this present day, in this very room, in your very hearts, speaking to the Life that is in the hearts of those sitting around you as well. For the life of the Church is a Trinitarian life that seeks to heal, to love, and to ground things in the source of all goodness and love, which is God, our creator, our savior, and our light in this world.