the Seventh Sunday after Easter

May 24th, 2020

Today’s readings are:

Acts 1:6-14

Psalm 68:1-10, 33-36

1 Peter 4:12; 5:6-11

John 17:1-11

If you don’t have a Bible handy, you can click on this sentence to find these readings.

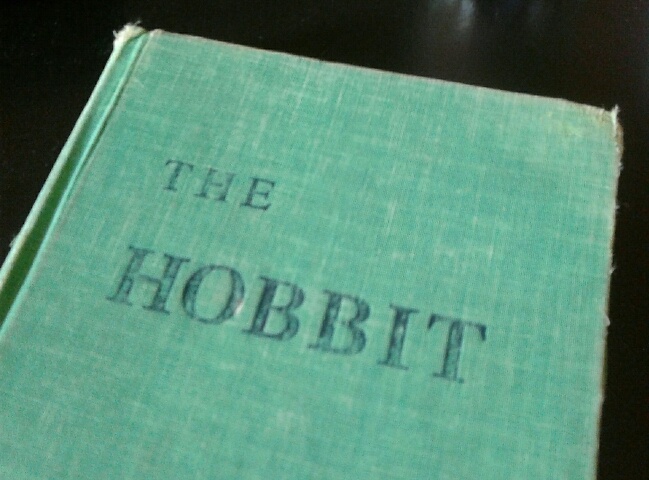

I brought a prop in today for my sermon. You all know I’m kinda a fan of Lord of the Rings and Tolkien, and this is the first book of Tolkien’s I ever read. It’s the Hobbit. It’s an old version of the Hobbit. You have to be real careful opening it. I’m not sure if you can hear online, but you can hear it cracking when I open the cover. And I’m not sure if you can see it, but the corners are all bumped up. The green of the cover has worn away, and you can see the cardboard underneath. And this is all a testament of years upon years upon years of reading this book.

I first read the Hobbit when I was in middle school. And I loved it. It was full of adventure, of dragons and dwarves and wizards. It excited me and moved me. I absolutely loved it.

Then I read it again in high school, and again in college, then again while traveling abroad, and each time, I learned something new about the book. It was still about dragons and dwarves and wizards, sure, but I saw that the journey of Bilbo Baggins was also about trust, about hope, about friendship and pushing on even when fear told us to run away. Bilbo’s journey spoke to my own fears, my own hope, my own life, just as all good literature does.

And then I read this story – this same story from this battered copy – to Gwendolyn. She was just born, and I had that aching parent-feeling that I wanted to share something with her that was meaningful to me. And you know what? This book that I had read time and time again, it still had room to grow. Reading it to my daughter, it became not just about me and about my hope, but spoke to the hope I had for my child, the fears and worries I had (and, if I’m honest, that I still have) as a father. It helped me understand those fears and face them.

I wonder if you’ve ever had a book like that? Some story that has followed you through your life, teaching you and guiding you. Or, maybe it’s not a book. Maybe it’s a recipe, something that your grandmother taught you to make, or that you made with your father on Saturday mornings. Or maybe it’s a sport. Maybe it’s football or baseball or soccer, this game that we as a country can come around, cheer for our team, and stick with that team through thick and thin. I remember my father-in-law’s devotion to the Mets, who lost so often but you know he tuned in to each game anyway, because they were his team since he was young. Whatever they are, these are things we grow with, that we learn to understand more and more fully, that seem to grow as we grow, even though they’re the same old game they were yesterday.

The world is deeper than we imagine. Beneath the surface of all things there are worlds to explore. This past Thursday, in our Greek and Latin Bible study, we read the Lord’s Prayer in Greek. Now, I know this prayer. I don’t remember a time when I didn’t know this prayer. My parents taught it to me before my brain could start making memories. I could rattle the thing off in my sleep. But when we slowed down, when we read this prayer word for word, stopped and pondered over each and every part of speech, we found that this prayer, that we all know so well, was new and fresh and beautiful. “Hallowed be thy name”, what does that mean? What does it mean to ask – to truly ask – for God’s kingdom to come on earth just as it is in heaven? And that most simple and common thing, bread, that we slop mayonnaise on or cut the crusts off of, that simple, simple thing bread – what if it could be the gateway to eternal life? What does that say about other common things, like the smell of cut grass, or the rain falling in the evening, or our neighbor, for whom God has as much hope as God has for you?

Jesus tells us that eternal life is prepared for us. And just when we might be reveling in this, our hand to our brow, “Wow, I mean, wow, that’s amazing! How can this be?” Jesus comes right in and says, “Yeah, so this is eternal life: to know God. To know God.

But is “knowing”, is “knowing” just a one-time thing? If you were to ask me, “Do you know the book the Hobbit?” I’d be like, yeah, I know it, I’ve read it. But is just having read the book really knowing it? You might ask me, “You know what baseball is?” and I’d say, yeah, sure, the game with the bat and ball, right? But then if you were to ask someone like my dad, who has loved the game since Mickey Mantle played, who coached kids to not just play it but to love it, who could imagine the crack of a bat or the smell of the field just as easily as I could imagine Bilbo Baggins playing at riddles with a dragon – he knows baseball.

“Knowing” isn’t just a one-time thing. It’s a lifetime spent in love. It’s a lifetime of turning the pages of a book and reading those words we know again and again and again. It’s sitting down with someone who we’ve seen so often that we could draw their faces with the most intimate detail, but who continue to surprise and delight us, to frustrate and test us, and who love us with a love that reaches beyond this world and back.

Jesus tells us that eternal life is prepared for all. And that eternal life is this: to know God. To learn more and more about the love, the hope, and the life that is at the center of all reality. To continue to get to know the creator of all things; to hang out with the one who died for us, who was raised for us, and who lives, even now, praying with a never-giving-up heart that we’ll stick around; to bring that love to others, to become love ourselves – these are just some of the ways that we can know God better.

And God is there, saying, come on, let’s sit down and grab coffee together and talk. Let’s go out for a walk beneath the blue sky that I created, because the sun is warm and the air fresh, and there’s just so much to talk about and to learn about each other. And hey, I heard your neighbor’s not doing well; let’s go see if we can cheer them up. And this isn’t just some vague call, some voice that comes and goes like the wind; this is the lord of life, God Almighty, the creator of heaven and earth, inviting you, you, to turn yet again, yet again, to love.