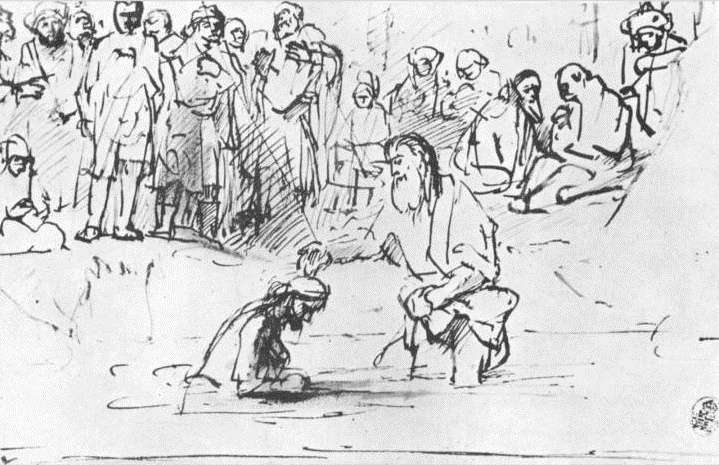

Sketch of Jesus being baptized, by Rembrandt

Isaiah 43:1-7

Psalm 29

Acts 8:14-17

Luke 3:15-17, 21-22

Click here to access these readings.

When we come to the world of the gospels, of the world where Jesus was born and lived, we come to a world of expectation. Now, this isn’t the same kind of expectation that we had in Advent when we were waiting for Christmas. Then, we knew when Christmas would be. We knew that Christmas would be on the 25th, and each day we would check off another day on our calendars. And as the day came closer and closer, we got more excited, maybe a bit more stressed and anxious that all would get finished, but the day of Christmas is set. It doesn’t move. It stays the same from year to year, and no matter how much more we have to get done, and no hard it is to wait, the day of Christmas remains the same.

The expectation of Jesus’ time was like this, but it was also different. It is, perhaps, a little more like waiting for a baby to be born. The doctors give you some vague day – April 14th…ish. Or around there. Maybe. But you never know. So when April comes along, even though it’s fourteen days until the due date, you start wondering: what about today? What about now? And as the due date gets closer, the doctors start saying, “Sure, but the baby could be late, too. Or early. Or on time.” Helene and I had our bags packed and in the car, but we didn’t know if we’d leave for the hospital on the 12th or the 15th or the 20th. Would it be morning? The middle of the night? During rush hour? We were expecting a great moment and a great change in our lives and in our family, and we only had a slight inkling of when that change would come.

The expectation of Jesus’ time was like this, but it was also different. You see, people in Jesus’ day were sure that the Messiah would come. Their Scriptures (which we know now as the Old Testament) said a lot about what the Messiah would do and how he would do it, but they didn’t say anything about “when.” Or, they did, but it wasn’t like with Christmas (“the Messiah will come on December 25th, in the year 2 A.D., at 11:23 p.m.”), nor did they have a rough estimate (“some time in the spring, probably”). They had this: soon. The Messiah would come soon. And that’s all they had to go on.

But there’s another difference, and this difference is important. I wanted Christmas to come because I love Christmas Eve service, and I love Christmas morning. I love exchanging gifts with my family and teaching Gwendolyn and Fiona about what giving means. I love thinking about and, again, teaching what Jesus’ birth into this world means. And with the births of my children, there was a lot of anxious waiting, but the thing we were waiting for was a new life in our lives. Their births would be a great change – I knew this – but it was all a lot of joy. For both, the time of expectation was good, sometimes tough, but overall really good.

But not all waiting is good. Not all waiting is joyful. The people of Jesus’ time were waiting, but they were waiting for salvation. And so it might be better to compare their expectation with that of a person waiting for a donor for a heart transplant. Or maybe a birth, but a birth with a lot of complications around it. For these people, waiting isn’t just a bit of anxiety before getting a good thing. They know something good is coming, but there’s a worry: what if it’s too late? I’m hurting so much now, how can I live in this pain? Why can’t God get on with it and give me some help? Why do I have to wait?

In this sort of waiting, there’s a lot of doubt and a lot of grief. And so when we come to Luke’s gospel, and we hear that the people were filled with expectation, we shouldn’t imagine, perhaps, everyone waiting in Times Square in New York City for the ball to drop on New Years Eve, but a man sitting alone in a waiting room praying “How long, O Lord, how long?” Is there joy in this expectation? Surely, but it might perhaps be better to call it hope, and a hope long fought for and struggled with.

For Jesus’ world was in pain. It was a world that had been ruled by a foreign empire for generations. It was a world that saw war and famine, disease and heartache. This world did not just wait for the Messiah – it longed for the Messiah. It didn’t just call out, “God, save us” but “God, come on and save us already!” Perhaps we can forgive them for running up to John and demanding, “Are you him, are you him, are you finally him?”

And it is into this expectation that Jesus does, finally, come. But it is important how he comes. Does Jesus come in, riding a tall, white horse, with a sword drawn? Or does he come with a great cape and a magic wand, ready to whisk away pain in an instant? No. He doesn’t. He comes in the midst of them. He comes where they’re hurting the most. He comes into their expectation and doubt and longing because he knows that we need that much more than we need a sword or a magic wand. Jesus comes to be present in our pain.

And this answers a pretty good question we might ask the Bible: why does Jesus need to be baptized? Baptism is about cleansing our sins, right? It’s about washing away the dirt and gunk and stains, isn’t it? And if Jesus is free of sin, then what is he doing in the Jordan river with everyone else being washed? And we’re in good company in asking this question, because John the Baptist asks it in Matthew’s gospel when he sees Jesus coming into the river. What are you up to, Lord? Why come into this dirty river with us when you’re so clean?

But that’s not how Luke sees it. That’s not how Luke sees Jesus’ baptism. For he looks at it and says, See, here Jesus is showing us that we don’t just need a bit of care or a nice pill that can take away the symptoms. No, Jesus shows us that real healing – healing that digs out the root of our pain and our suffering, that answers those longings for help that go to the heart of our souls – that sort of healing is found only in God being born within us. And to do this, God doesn’t just stand by us in our pain but enters into that pain. God doesn’t just pat us on the hand and say, “There, there”, but cries with us, cries out with us, sits up all night in expectation with us, and not just with us, but in us. It’s like how you make sweet tea in the south. You don’t make tea and then add the sugar in later. No, you add the sugar in while you’re brewing it, so that it’s not just a little sweet additive that’s sprinkled on top but cooked deep into the tea. The sugar and the tea become fused together, so that one can’t be taken from the other.

And this is how God asks us to be with the world in our own ministries. We don’t leave the door of the food bank open with a sign that says, “Take what you need.” No, we are present in the room, talk to the people, and hand them a bag of food from our own hands. Or, when new people come into our food ministries here, be it Emmaus Meals or Prayer Breakfast, we don’t give them a plate and shoo them out the door. No, we invite them to sit with us, to tell us their story, to join in our conversation, and we tell them our story as well. Doing ministry means getting into people’s lives, living with them, and walking with them.

We can think of many ways to express this. We can bring up a lot of different images and ideas and speak till we’re blue in the face. But at the end of the day, we can just quote Isaiah when he writes, “And God said, ‘I love you.’”