Ash Wednesday

March 26th

Today’s readings are:

Isaiah 58:1-12

Psalm 103

2 Corinthians 5:20b-6:10

Matthew 6:1-6, 16-21

Click here to access these readings.

I want Easter. I want it to be Easter. I want the colored eggs, the little green grass made of plastic. I want pastel colors. I want white vestments and alleluias and that bright, spring sunshine to be inside the church as much as it is outside. I want Easter, when Jesus is alive and the whole world is changed. I want an empty tomb, I want the flaming tongues of Pentecost, I want Jesus alive and well and joyful.

But here we are. It is Ash Wednesday. We have over a month of Lent before us, we have over a month of Lent between us and that open tomb, that Jesus alive and joyful and that hope of the world after his Resurrection. And today, as Lent begins, we do not have the bright spring-white vestments of Easter but the dark, purple, penitential ones of Lent.

We are an Easter people, aren’t we? Aren’t we? We’re a people who live in the light of the Resurrection, a people who live in a world where death has died, where hope unlooked for because it’s just too good to be true, where that hope and that love have thrown open the gates of death, shattered the bonds of sin and darkness, and led us into a life of light and life. We are an Easter people, so what are we doing with the soot of death upon our foreheads?

I’ve preached lately on why Lent is a good and healthy thing. I’ve preached about how we need to take stock of our relationship with God. And we do this not because we’re scared of getting into trouble or because, as if God were a strict teacher and is going to send a bad report card home to an equally strict parent. No, for, again, we are an Easter people: our relationship with God is one of love, that is founded and fashioned out of love. And relationships founded on love are endlessly deep. Lent is the time when we explore that love, see how we can enter into that love more fully, more openly, so that we become that love ourselves. Goodness, could you imagine becoming love? That’s what we’re called to. That’s what we’re called to as Christians. To become love.

Yes, we are an Easter people, but we are living in an Ash Wednesday world. Because of Jesus Christ, death no longer has dominion over us. We are free from it, free from the binds of death; but death still hurts. Darkness is still a cloud that confuses us and turns our hearts to worry, anxiety, and hatred. We humans still hate those who are different than us, sling ugly words at those we don’t understand. We still beat people and abuse people emotionally, physically, mentally, and spiritually. And there are people in this world who hate themselves and see only darkness before them. We live in a hard world.

And it’s good to remember this, not because we need to hate the world, too, or because we need to cut ourselves loose and just look forward to the joys of heaven, to grin and bear the pain of the world because the afterlife’ll be worth it. No, we need to look at the hard, ugly, hateful world, and that hart, ugly, hateful world inside of ourselves, because Jesus Christ came not to condemn the world, but to save it, to tell you that all things, all things, are worthy of the love of Christ. You are loved, not because God forgets your sin for a while but because God loves you. All of you, every – last – bit.

The world needs to hear this. People need to hear this. Have you ever had the privilege to tell someone, someone who thought themselves unworthy and forgotten, that they are in fact precious and beloved of God? It is a grace and an honor to do so. It is a gift. And you know what, it is also the mission of all Christians, no matter what creed or denomination, to do this: to enter into the darkness, to even the darkest parts of human existence, be it in the world around us or in our own hearts, and to dispel that darkness with love. And I don’t mean some greeting card love, but a love that is strong and that looks death and despair in the face and says, “No, you are nothing against the light of this love.” For that love is true reality; for God is love.

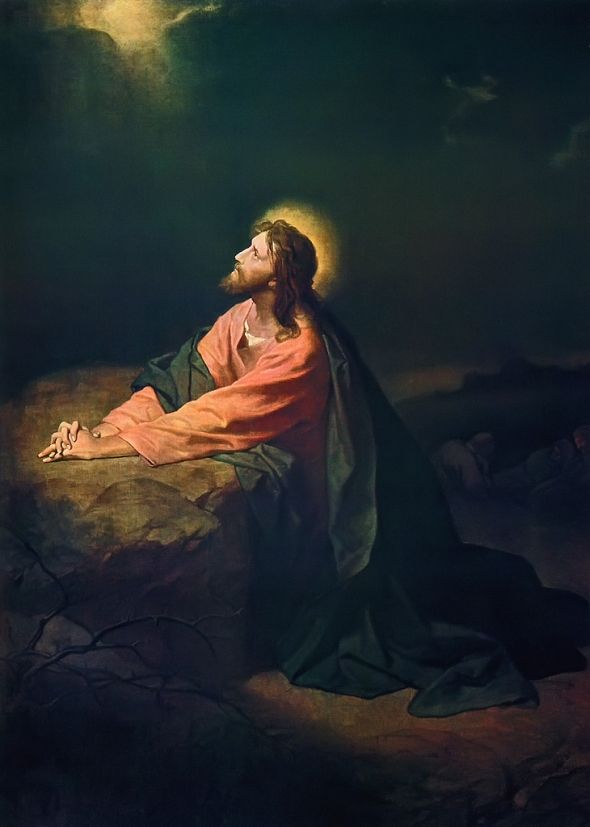

And so today, Ash Wednesday, we look death in the face. And part of looking death in the face is realizing that it is still painful, and that for some, that pain is deep and it is real. But we look death in the face because we have already looked Life in the face, and we know it to be a person, a person of love, and we know him to be stronger than death.

I could end here, but I want to say one more thing. I hope that these words, and this service, has grounded you in the Love and Life that is past death. I hope that our time here on Ash Wednesday has filled you with a renewed purpose, so that you will enter into a holy Lent and look forward to the Joy of Easter. That may be the case for some of you, but it might not be for others. Looking death in the face is hard, and so I want to say: you are not alone. We do not look death in the face alone as individuals but as the Church. If looking at death has stung you, or hurt your, or if you are afraid, remember that we are here for you, both I as your priest and us as your fellow siblings in God. Nor are we alone, for God himself has looked death in the face from the cross. And he stands now among us as our brother Jesus, in whose hands is real bread, and in whose voice is the salvation of all.